Welcome to Art Song Canada, an online “magazine” to cover various aspects of the art song world. A new issue is published quarterly. Please consider subscribing for free now.

ןעװעג זיא רשפֿא סאָד ןײַמ קילג :

Geven iz efsher dos mayn glik:

Perhaps this was my happiness:

ןליפֿ יװ ענײַד ןגיוא

filn vi dayne oygn

to feel how your eyes

ןבאָה ךיז ראַֿ פ רימ ןגיובעג .

hobn zikh far mir geboygn.

bowed down before me.

ןיינ , ןעװעג זיא סאָד ןײַמ קילג :

Neyn, geven iz dos mayn glik:

No, rather this was my happiness:

ןייג קידנגײַװש ןיה ןוא רעה

geyn shvaygndik hin un her

to go silently back and forth

טימ ריד ןרעביא רעװקס .

mit dir ibern skver.

across the square with you.

ןיינ , טינ סאָד , טינ סאָד , ראָנ רעה :

Neyn, nit dos, nit dos, nor her:

No, not even that, but listen:

ןעװ רעביא רעזדנוא דיירפֿ

ven iber undzer freyd

how over our joy

טגעלפֿ קידנעלכיימש ךיז ןגיובנײַא רעד טיוט .

flegt shmeykhlendik zikh aynboygn der toyt.

there hovered the smiling face of death.

ןוא עלאַ געט ןענײַז ןעװעג ןרופּרופּ ,

Un ale teg zaynen geven purpurn,

And all of the days were purple

ןוא עלאַ רעװש .

un ale shver.

and all were hard.

– Anna Margolin’s “Mayn Glik,” transliterated and translated from Yiddish by Shirley Kumove, featured in Alex Weiser’s and all the days were purple

December is upon us! And with it, we continue to look at art songs that expand our definition of the art song canon. Today’s issue focuses on works from minority linguistic communities in Canada, including Bulgarian, Farsi, Irish, and Yiddish.* We are very pleased to present four up-and-coming singers/singer-scholars’ introductions to art songs in languages that reflect their backgrounds and exemplify just a few of the cornucopia of traditions present within Canadian society. Firstly, soprano and scholar Dr. Maeve Lilian Palmer gives us a primer on Irish song in 2025, including a guide to pronouncing all those Irish songs we know you’ve been longing to sing. Then, Lebanese-Palestinian Canadian tenor Haitham Haidar discusses his experiences melding his Arab background with the Western classical canon within his new (gorgeous!) album Zaytoun. Soprano and PhD candidate Jardena Gertler-Jaffe rounds things off with an introduction to the rich world of Yiddish art song, and finally in our “Introducing…” column, soprano and Speech-Language Pathology professor Theodora Nestorova introduces us to a Bulgarian work by her great-uncle, Tsanko Tsankov’s “Жениш ме, Mамо, годиш ме” (“Mother, You Are Giving Me Away”).

As always, we hope this issue inspires you and reminds you of the boundless potential of the art song genre. If you enjoy this issue, please consider donating to support the Art Song Foundation of Canada’s bursary programs for young Canadian singers and pianists.

— Sara Schabas, editor

* we may need to do a sequel issue soon!

An Introduction to Irish Art Song by Dr. Maeve Lilian Palmer

On a particularly wintry day this November, I braved the unseasonable snow to attend an Irish gathering at Midtown Toronto’s Boxcar Social (spearheaded by Pa Sheehen, Assistant Professor at St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto). I hadn’t been to the gathering in some time, so, as I climbed the narrow steps, I recalled the small, socially distanced walks around Queen’s Park of 2020, often just two or three people strong. I wondered if a similar group might be cozied up in a small corner near Boxcar’s fairytale patio. Yet, as I shook off my snowflaked hair and entered the warmly lit bar, I began to catch bits of Irish all around me. A group of elegant young women, drinks in hand, some be-sweatered lads by the window, a venerable group chatting jovially by the stairs. Astonished, I chanced a “Dia duit” (hello) to a pink-clad white-haired woman who returned “Dia is muire duit” (hello to you)! Once I had acquired a frothy chai tea, I made my way to the usually quieter upstairs, where Irish speakers overflowed every room, crowding out the bemused, laptop-laden regulars. From native Gaeilgeoir “Irish speaker” immigrants, to new language learners reading Irish picture books in a pillowy corner, dictionaries in hand, the voice of an teanga beo “the living language” resounded.

Once mother tongue to nearly a quarter of Canadians, Irish-Gaelic (Irish), like many native languages of Canadian Indigenous and immigrant peoples, suffered under Canada’s Anglo and religious assimilation efforts. Punitive policies and pervasive sentiments casting Irish as ‘subversive’ and ‘backward,’ inflamed the already fragile state of the language following the Great Irish Famine, contributing to its dormancy in 20th century Canada. As Canada enters a period of reconciliation with minority and Indigenous languages, the shroud of silence lifts and Irish sounds again; colonial wounds in Ireland and the Irish diaspora are, with effort and joy, beginning to heal.

Still, should you have counted yourself among those who thought Irish merely an accent, or else long dead, and certainly not a language of Canada, you wouldn’t be alone. Despite Canada’s ongoing revival of Irish in speech and song, the aptly named “Great Silence” of the 20th century continues to influence song performance in Canada. Popular classical arrangements of macaronic songs (songs in two languages – in this case Irish and English), often obscure Irish text beneath unstandardized transliterations. Perhaps you’ve performed John Beckwith’s “Dimindown” from his cycle, Four Love Songs, only hoping you had the syllabic pronunciation correct. Or maybe you’ve performed a 20th century publication of The Gartán Mother’s Lullaby, arr. Herbert Hughes, a staple of RCM level 8 students, not realizing the transliteration “a lyann van o” is the poor baby to whom the mother sings (a leanbhán ó “oh my little child” / a leabh an-óg “my babe in arms”). While possibly well meant, transliterations from any language are difficult to decode. It’s time to publish words, not transliterations, so we might strengthen our relationships with minority language and song, and begin to heal colonial wounds in our artistic practices.

For many, Irish song brings to mind the native Irish tradition of sean-nós singing: atemporal solo airs with mellifluously ornamented melodies, and a physically reserved performance practice. Today, sean-nós and other Irish traditional genres are joined in language by innumerable musical styles: rap, new age, pop, world fusion, choral, opera, Sean-nós–Western Lyric fusion, and, to our purposes, art song, have all joined the fray.

The journey of Irish into Western Lyric styles reflects the history of colonization and reparations in Ireland. Consequently, piano-vocal Irish language Art Song is a developing repertoire. Significant in 21st c. Irish art song is the 2019 Tionscadal na nAmhrán Ealaíne Gaeilge “Irish Language Art Song Project,” spearheaded by Dáirine Ni Mheadhra, co-founder of Canada’s now-dissolved Queen of Puddings Music Theatre. The project commissioned an impressive fifty Irish art songs from eighteen composers, including multinational Canadian composers Ana Sokolović, Ashkan Behzadi, and Anna Pidgorna. The songs, scored for voice and piano are open access, with translations, IPA transcriptions, and both spoken and sung audio recordings, making them highly accessible and programmable.

Ashkan Behzadi, Trí Amhráin ar Dhánta le Micheal Hartnett, 1. Sneachta Gealaí ‘77

Anna Pidgorna, Amhráin Chaointe 1. Caoineadh Eibhlín

Ana Sokolović, Trí amhrán 2. Maileo Léró

Notable among the commissioned is Irish composer Linda Buckley (Sólás) (Sólás 2. Sólás Buckley ). Buckley is known for her seminal work in the genre of sean-nós-western lyric fusion, through her collaborations with sean-nós singing Iarla Ó Lionáird, a prolific sean-nós singer, producer, and champion of contemporary sean-nós fusion works. Check out Buckley’s composition Ó Íochtar Mara / From Ocean’s Floor, for sean-nós singer and orchestra. Other groundbreaking collaborations with Ó Lionáird include 2026 Grammy nominated composer Donnacha Dennehy’s Grá agus Bás written for Crash Ensemble and sean-nós singer, and his docu-cantata “The Hunger” combining both bel-canto and sean-nós singing, starring Dawn Upshaw and Iarla Ó Lionáird. As yet, Dennehy does not have piano-vocal Irish language art song listed on his website – if you see this Donnacha, this is my plea to you!

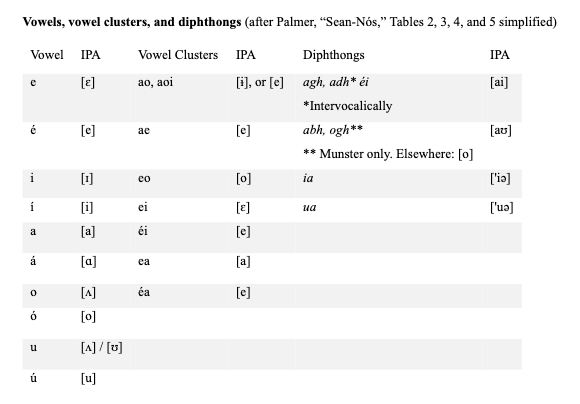

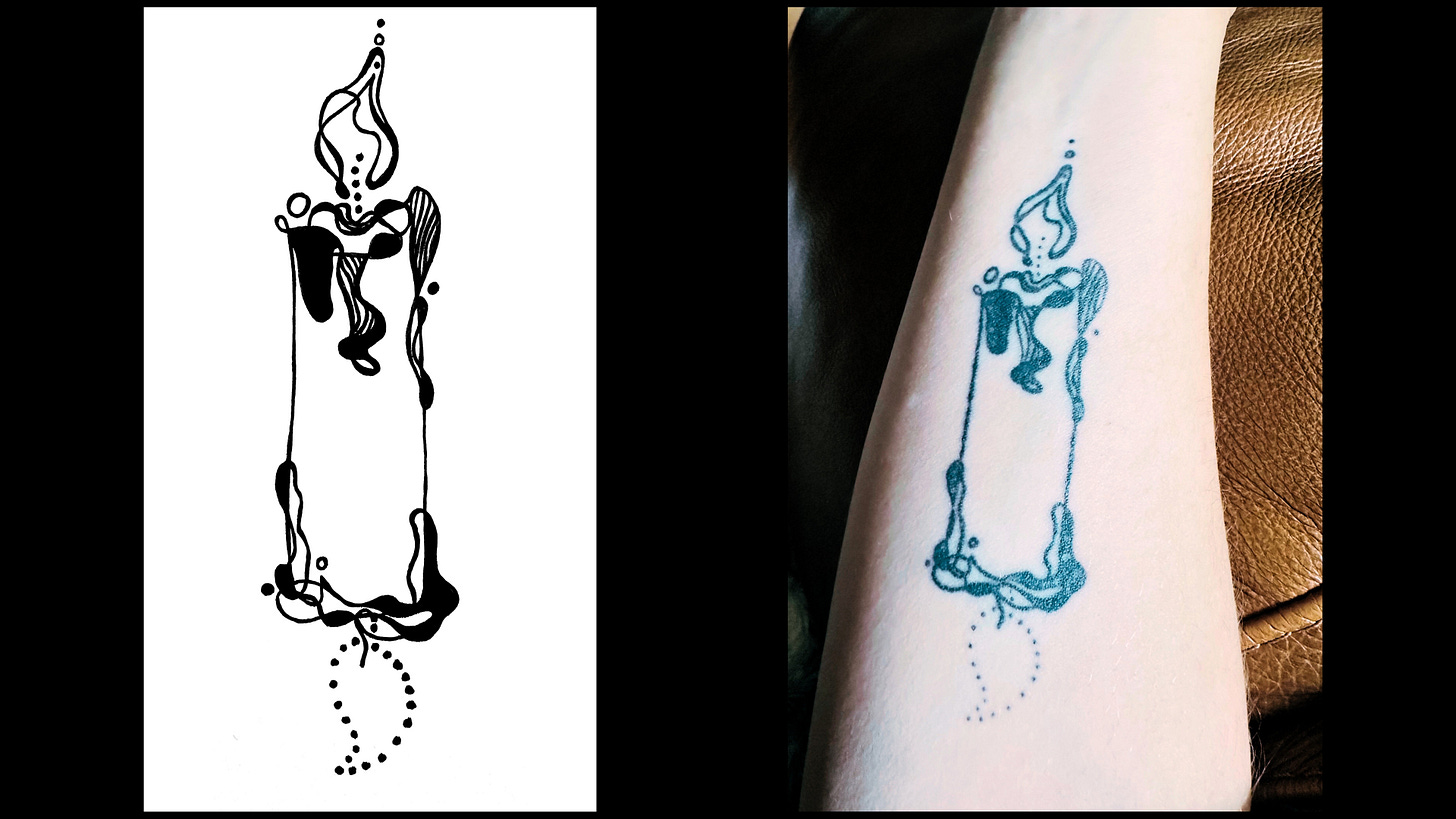

Beyond this project, you’ll find a wealth of Irish song and choral music through Ireland’s Contemporary Music Centre, though without the pronunciation guides. However, while grammatically complex, Irish has exceptionally clear spelling rules. Though simplified, and non-dialect-specific, I offer these diction charts as a starting point for singers beginning their journey in Irish song.

As the Great Silence lifts, I look forward to Irish and other minority and Indigenous languages taking centre stage in recital repertoire. If my experience at Boxcar social is any indication, the future for Irish in Canada is a bright one.

Go leigheasfeadh glór do bhéil… “May the sound from your lips heal…”

A PRIMER ON IRISH PHONETICS

Doyle, Danny. Míle mile i gcéin: The Irish language in Canada. Ottawa: Borealis Press, 2015.

Palmer, Maeve L. “Singing Sean-Nós.” DMA diss., University of Toronto, 2024.

“Triple-threat … coloratura” (Opera Canada) Maeve Palmer is known for her sparkling voice and stage presence. An alumna of the Rebanks Family Fellowship and the University of Toronto Opera School, Maeve has performed with Opera Atelier, Tapestry Opera, and Chorus Niagara, among other companies. Recent roles include Valencienne (Lehar’s The Merry Widow, Highland’s Opera Studio), Aunt Lydia (Ruders’ Handmaid’s Tale, Banff Centre), and Genio (Haydn’s Orfeo ed Euridice). An acclaimed interpreter of art song and traditional Irish song, Maeve is a recipient of the Jim and Charlotte Norcop Prize in Song (UofT). Maeve holds a doctorate in Voice Pedagogy and Performance from UofT where she researched Irish traditional singing while residing as a Junior Fellow at Massey College. Currently, Maeve is thrilled to be teaching English Art Song at the UofT.

Candlelight: in search of identity by Haitham Haidar

Being an Arab immigrant in North America brings its own set of oppressive challenges that continue to ask me to assimilate and cater to a system that ultimately does not serve me or my people. I spend so much time turning my thoughts and feelings into palatable appetizers (not too much) in hopes of not ruffling any feathers, of not further giving this society reason to dehumanize us. Suddenly, I am not one, but two. I am the Lebanese-Palestinian, Arab man who was raised in Beirut under a combined sky of stars and rockets. I am also the Canadian, North American-looking, easy-going man whose English is “really good!” This division of self, this compartmentalization, is a safe space where both identities can be tucked away safely when needed. Unlike candles, these identities feel like they cannot exist while the other one is shining bright. That notion of needing to quiet one part down to uplift the other is something that brings unnecessary strife and dissonance to my world, and I aim to keep exploring an identity that contains all parts of who I am.

Identity through language

The stories we tell are windows into our humanity: They are the coffees we prepare in the morning, they are the overheard arguments on the street, they are the sound of the sea waves crashing against the coast. We use words to describe how feel and what we think.

Language is a means of expression, not expression itself, grasping for sonic syllables to make sense of how we feel and how we want to share it. Feelings are wordless, they are deep physical and soul-full rushes of heat in the body. They travel in our minds attempting to be labelled and categorized, searching for words to do their expression justice. But do we ever express our feelings or thoughts in their truest forms? Does verbalizing one’s feelings mean the same thing as expressing them? How else can one express their thoughts if not through language?

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” – Ludwig Wittgenstein

Identity through music

For those of us who grew up somewhere other than North America, our dive into classical music came from a yearning to explore belonging. Since we don’t feel like we are welcome on this geographical earth, maybe we are looking for a point of connection through music, another language. Within that, are we still assimilating as we yearn to find ourselves? What parts of us do we lose when we dive so deep into a world that was never meant to be ours? Our cultural stories become “folk tunes” or “traditional Arabic music” or even credited to “anonymous”. Is that true? Or is it only because they weren’t composed by Schumann or Debussy? Our music from our homes is rooted in generational trauma, joy, celebration, and sorrow. The music itself is coded with love letters and stories that transcend the power of the spoken word. This music continues to connect those of us living far from our lands to our families and our people.

“If a composer could say what he had to say in words he would not bother try to say it in music.” – Gustav Mahler

Identity through Zaytoun (alignment):

Zaytoun is a playground of cultures, of identities. Once separate and individualistic, these identities become intertwined, aiming to further connect with one another. Musically, it is the representation of my own personal search for belonging, for home, for a true connection to my roots. One part lives in the Western Classical music system, and the other is rooted in generations of Arab artists and thinkers.

“Zaytoun is all of these things combined. It joins the heart and soul of my Arabic roots with my love and dedication to Baroque music. Zaytoun explores the interlaced nature of Arabic and Baroque music in a way that feels new yet natural and allows us to shorten the distance between these two worlds.” – Zaytoun liner notes

As the process of producing and artistically executing Zaytoun developed, I found myself trying to label and categorize this album: is this considered “world music” or “early music”? Is it classical enough for that? Is it too out there to neatly fit into a box?

I counter all these doubts with questions like “why does it matter?” That short question alone invites me to reexamine the need to label and categorize, perhaps even to assimilate. Am I subconsciously attempting to assimilate Zaytoun into the Western canon of classical/early music? Is that an inadvertent attempt to make my cultural musical exploration more palatable to the audiences I’ve been taught to cater to?

Zaytoun, the olive, small yet mighty, is the perfect connector between my two worlds rooting me in my ancestor’s wealth of knowledge and helping me expand that into a world that is finally seeing us as human.

Perhaps Zaytoun can remind us that in our differences we are very much alike.

Haitham Haidar is a Lebanese-Palestinian Canadian tenor highly sought out for his musicality, “standout presence”, and sensitive storytelling. He is a proud graduate of Yale’s Institute of Sacred Music, McGill’s Schulich School of Music, and the University of British Columbia and currently resides in Montreal, Quebec. Haitham is praised for his ‘musical and linguistic versatility’ and his ‘bright’ and ‘innately lyrical voice’ and enjoys performing oratorio, opera, and chamber music across North America, Europe, and Asia.

A Brief Introduction to Yiddish Art Song by Jardena Gertler-Jaffe

Yiddish art song can roughly be divided into two categories: works that draw on folksong materials and those that use texts from the modern Yiddish literary tradition. Yiddish cultural production is diverse, and art song occupies a space distinct from theatre, popular music, and folksong– areas that have themselves been the subject of renewed study, performance, and attention. The following overview offers a brief introduction to this repertoire by highlighting representative works from both categories.

Although Yiddish has existed for over a thousand years, most of its literary output emerged within the last century and a half. This relatively short timeline reflects the evolution of Judaic practice and the multilingual nature of historical European Jewish communities. The progenitors of classic Yiddish literature, Y. L Peretz, Mendele Mocher Sforim, and Sholem Aleichem, were active during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and their work set the stage for an explosion of modern Yiddish poetry.

Settings of Y. L. Peretz’s poetry for children by Russian Jewish composer Moses Milner (1886–1953), performed by soprano Lucy Fitz Gibbon and pianist Ryan McCullough.

Modern Yiddish poetry proved to be fertile ground for art song setting. Lazar Weiner (1897, Ukraine —1982, New York) stands out as a central figure in the development of Yiddish art song. His prolific catalogue includes more than two hundred songs written for voice and piano. Although he set a wide range of poets, he was particularly immersed in American Yiddish modernist literary culture, composing songs to texts by Mani Leib, Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, and Naftoli Gross of Di Yunge (The Youth) movement, as well as Jacob Glatstein and Aaron Leyeles of the In Zikh (Inspectrovist) poets.

‘Shtile likht’ (1956) by Lazar Weiner on text by Mani Leib (1883, Ukraine—1953, New York). Performed by soprano Ida Rae Cahana, and pianist Yehudi Wyner (Lazar Weiner’s son).

Yiddish modernist poetry has been the source of continued inspiration for composers. This poetry often features writers coping not only with the radical changes in life arising from the technological advancements and industrialization of the early twentieth century, but also the alienation, isolation, and disorientation stemming from a shared history of immigration and displacement as artists fled anti-Jewish violence in Europe. Mikhl Gelbart (1889, Ozorków, Poland—1962, New York) provides a window into this world. In his song New York, setting poetry by Aaron Leyeles (1889, Włocławek—1966, New York), Gelbart captures both awe and repulsion in response to the city’s frenetic sounds and sights.

Anne Slovin, soprano and Andrew Voelker, piano performing ‘New York’ (1932) by Mikhl Gelbart.

Contemporary composers continue to expand the tradition. Alex Weiser (b. 1989), composer and leading advocate for Yiddish art song, has likewise turned to texts written by poets enmeshed in modernist literary movements. ‘Mayn glik’ from his cycle and all the days were purple sets poetry by Anna Margolin (1887, Belarus—1952, New York), a poet associated with both Di yunge and the Inzikhistn. Weiser’s musical language places Yiddish in a distinctly contemporary aesthetic, using colorful yet minimalist harmonies to foreground Margolin’s contemplative text.

Eliza Bagg, vocalist, and Marika Bournaki, pianist perform ‘Mayn glik’ (2017) by Alex Weiser.

Yiddish folksong has also served as a rich source of material for art song composition. Today, many composers find folksong materials in the audio archives of organizations such as the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and the Milken Archive of Jewish Music. When Dan Shore composed his set of Yiddish folksong-based art songs , he turned to an archive of audio recordings made by folklorist Ruth Rubin. Shore’s work faithfully renders the melody and texts as they were sung to Rubin by Anna Berkowitz in her Montreal home. His piano accompaniment provides a beautiful harmonic foundation to the melodic material, and at times, countermelodies appear that flesh out the affective qualities and provide variation to these strophic songs.

Five Songs from Anna Berkowitz’ (2021) by Dan Shore (b. 1975), performed by Jardena Gertler-Jaffe, soprano, and Diana Borshcheva, piano. In this 2021 virtual premiere, each song on the set is preceded by the archival recording of Anna Berkowitz singing the folksong.

Other compositions using Yiddish folksong may use it only as the very basic foundation of their work. Alex Weiser describes this as a “free fragmentation” approach, in which a piece keeps only a general connection to the source folksong material but is otherwise freely composed. Aaron J. Kernis’s (b.1960) work “Farewell” (2019) exemplifies this method. Kernis draws on the instrumentation and initial melodic material from a 1909 arrangement written by Joel Engel (1868—1927, Russia), who was one of the founders of the Society for Jewish Folk Music. Kernis transforms the material into something decidedly different from the original folksong, incorporating whispering, chromaticism, and ornamental melismatic passages.

‘Farewell’ (Zayt gezunterhayt) by Aaron J. Kernis, performed by Jardena Gertler-Jaffe, soprano, Weichao Zhu, violin, and Ji Young Lee, piano.

The world of Yiddish art song is steadily growing. In a recently compiled list, over eighty works written in the last twenty years alone fall into this category, including works by Canadian composer Jérôme Blais. The source material for Yiddish art song is varied and plentiful. Singers, pianists, and composers intrigued by this brief overview are encouraged to delve more deeply into this remarkable trove of poetry and song.

A BRIEF PRIMER ON YIDDISH

Yiddish is the historical language of Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jewry. It is estimated to be roughly a thousand years old, arising from the European period in Jewish History. Yiddish is a Germanic language written in Hebrew script, with significant borrowed linguistic components from Semitic, Slavic, and Romance languages. Historical Jewish language communities have generally been at least tri-lingual. In most pre-Holocaust Eastern European contexts, Yiddish would have been spoken in the domestic sphere as a Jewish secular language. In contrast, biblical Hebrew would have been used for religious study, and secular, non-Jewish language might have been reserved for communication with non-Jewish folk.

On the eve of the Second World War, Yiddish was the third-most spoken Germanic language in the world. More recently, UNESCO has described the language as “definitely endangered”. The reasons for this are manifold, but include the rise in prominence of Modern Hebrew, which arose with Israeli nationalist efforts, the suppression of Yiddish language and culture in Soviet Russia, and a strong internalized push towards assimilation in Jewish diasporic communities. Still, Yiddish survives. Yiddish is spoken as a vernacular in the highly insular Hasidic communities around the world. And, there are many people, including myself, who did not learn Yiddish at home despite having parents or grandparents who spoke the language, and who have immersed themselves in the study of Yiddish as a way of celebrating and continuing the Jewish diasporic culture.

Canadian/American soprano Jardena Gertler-Jaffe is a multi-faceted artist and scholar. Jardena’s recent performance work includes singing the roles of Krystyna Zywulska in Jake Heggie’s opera Two Remain, Marzelline in Beethoven’s Fidelio, a recital inspired by the life of Alma Mahler with pianist Erika Switzer, and workshopping the roles of Gitl in Dan Shore’s Greeners and Thea in Danika Loren’s Hedda. Jardena made the Canadian premiere of Alex Weiser’s Pulitzer-nominated set and all the days were purple, and the world premiere of Dan Shore’s Five Songs from Anna Berkowitz, works that also align with her love of and interest in Yiddish language and culture. She holds music degrees from the Bard College Conservatory (MM) and the University of Toronto (BMus). Jardena is an alumna of Bard Summerscape and Sarasota Opera’s Apprenticeships, the Britten-Pears Young Artist Programme, and the Association for Opera in Canada Emerging Artist Fellowship. Jardena is a PhD student in Music Performance at New York University, fully funded by a competitive Steinhardt Doctoral Fellowship. Jardena earned her MA in Ethnomusicology from the University of Toronto. Jardena has been on the staff of the art song champion organization Sparks & Wiry Cries since 2020.

Tsanko Tsankov’s “Жениш ме, Mамо, годиш ме” (“Mother, You Are Giving Me Away”) by Theodora Nestorova

Soprano Theodora Nestorova and pianist Margarita Ilieva’s performance of this art song recorded at the Bulgarian National Radio.

“Жениш ме, Mамо, годиш ме” / “Zhenish me, Mamo, Godish me” (“Mother, You Are Giving Me Away”) is a rarely heard art song by Tsanko Tsalov Tsankov (1899-1967)—a Bulgarian composer and musical theorist whose life bridged Europe and Canada. Despite facing sociopolitical and familial persecution during the Communist regime, Tsankov became one of Bulgaria’s most influential musical leaders: a conductor of the Vienna Opera (1942), rector of the Bulgarian Music Academy (1940–43), and co-founder of the Society of Bulgarian Composers (1933). Rooted in the colours of Bulgarian folk music, this song exemplifies the speech-like phrasing typical of early 20th-century modernism, framed by modal lyricism and asymmetrical phrasing. This reflects the period’s synthesis of Western European art music techniques with Bulgarian folk modalities (rich harmonic and timbral textures with uneven metres and intricate rhythmic patterns). After World War II, Tsankov’s immigration to Ontario (where he taught as a professor) with his wife, soprano Karin Mayer, and his daughters, one of whom was concert pianist Dolya Tsankov, situates this musical work within a broader transnational legacy. As Tsankov’s great-niece, I present this heritage piece as a culturally significant artifact to Canada’s expanding repertoire of diasporic art song traditions.

Bulgarian-British-American voice scientist, pedagogue, and performer Theodora Ivanova Nestorova serves as Assistant Professor of Speech-Language Pathology at Viterbo University. With award winning published research and recorded albums, Theodora serves as Associate Editor of the NATS Journal of Singing Mindful Voice column. Theodora is a former Fulbright Scholar and holds a Ph.D. from McGill University, M.B.A. from Global Leaders Institute, M.M. from New England Conservatory, and B.M. from Oberlin College & Conservatory. More at theodoranestorova.com.

Editor’s note: Readers, do you have a little known song cycle you’d like to share with the Art Song Canada community? Write to us at [email protected] to be featured!

Please consider making a contribution to the Foundation today.

The shining of gold, dark

and blinding bright by turns,

the sun falling from blue clouds

into the ocean and noon and dawn,

all unfolded and held up, carried, offered on motionless

petals, fingers, rays, unchanged

through all the day’s seasons

and the night under spectral

low-watted garden bulbs.

– from A.F. Moritz’s “Marigold,” featured in James Rolfe’s Wound Turned to Light

Happy September, readers! In this issue, we close off our Canadiana summer by looking at Canadian works that are coming to define the first quarter of the 21st century. James Rolfe—the Juno-nominated Canadian composer known for his operas The Overcoat, Swoon and Aeneas and Dido, as well as his many songs—takes us inside the eclectic mind of a composer in an article with references ranging from Hildegard Von Bingen to Toru Takemitsu, Leonard Cohen, Edgard Varèse, and the Canadian metal band The Dayglo Abortions. Following James’ piece, the mezzo-soprano and co-founder of Musique 3 Femmes, Kristin Hoff, offers an intimate look at Ana Sokolović’s Love Songs; a piece which pushes the boundaries of art song and opera and is quickly becoming a 21st-century classic. Finally, the label-defying soprano-composer-artist and creative force Danika Lorèn tells us how art song has shaped their spirit, both as an interpreter and as a creator.

Once you’ve finished reading all of that, keep scrolling to read our “Introducing…” column from Montreal-based soprano Marian Guay, who offers us a bilingual introduction to the 19th-century composer Liza Lehmann’s Bird Songs.

As always, we hope this issue inspires you and reminds you of the transcendent, boundless potential of art song. If you enjoy this issue, please consider donating to support the Art Song Foundation of Canada’s bursary programs for young Canadian singers and pianists.

— Sara Schabas, editor

Filth, Joy, and Singing by James Rolfe, composer, August 2025

In July 2025, I acted as composer-mentor for Toronto’s Tapestry Opera Librettist-Composer Workshop—better known as the Lib Lab—led by Artistic Director Michael Mori. Four composers and four writers took turns pairing off with one another. The writer had 24 hours to create a libretto for their composer, who then had 24 hours to compose a 5-minute operatic scene. The four rounds were spread over ten days; each round was launched with a different prompt.

On the first morning, Michael and I both read an article in The Guardian on Hildegard von Bingen, the 12th-century German nun, composer, homeopath, and mystic.1 From an early age, she experienced visions, possibly caused by migraines. The image that stayed with me was the voice of God telling her “O fragile human, ashes of ashes, filth of filth, say and write what you see and hear”. It’s a beautiful metaphor for creation, for trusting in the unexpected places your imagination will take you. But I confess I was much more excited by the word “filth”: such a resonant, powerful word, and so dissonant with the image of God’s voice. I thought of my grandson who, not yet three years old, ran into the back yard and shouted “Poo!” at the top of his lungs. Who knows what he was thinking? I imagine he felt joy, a joy in his power to create and re-create his own filth—in psychoanalytic terms, a metaphor for the creative process. And perhaps the poo-triggered explosion of joy was so violent that he had to give voice to it. He’s learned that adults devote a lot of attention to keeping him clean, and that filth is shameful and naughty and funny, magnifying its psychic energy. And he’s young enough to have a very expressive (and very powerful) voice.

James Rolfe’s “Burning In This Midnight Dream” Wound Turned to Light, poem by Louise Halfe, sung by Jeremy Dutcher, piano Lara Dodds-Eden.

And so we had our second prompt: filth. The four pairs responded with wildly varied scenes, ranging from hilarious to absurd to dark. In comparison with the first assignment, there was a sense of liberation and loosening up. Perhaps the collision between filth and purity released dramatic and operatic energy.

Classical musicians are taught to purify: to make our art distilled, timeless, to rise above the mundane. Yet singers learn that pure voices can also get boring, that emotional connection lives in “the grain of the voice”. (There is a Roland Barthes essay of the same name, lovingly describing how certain old recordings of Schubert song cycles could touch his heart in a way that the more celebrated Fischer-Dieskau couldn’t.) A bit of grit can make a voice more real, more connected to the lyrics. For their part, composers learn how asymmetry and awkwardness can draw in the listener; if musical sailing is too smooth, we fall asleep at the rudder. To quote a Canadian composer, “There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.” (Leonard Cohen, from his song Anthem.)

“Marigold” from James Rolfe’s Wound Turned to Light, poem by A. F. Moritz, sung by Alex Samaras, piano Lara Dodds-Eden, video by Juliet Palmer.

Some musicians aren’t afraid to roll in the filth. I think of the Victoria, BC punk metal band The Dayglo Abortions and their album Two Dogs Fucking: their way of shouting “Poo!”. When I first heard the music of Edgard Varèse, I disliked its extreme registers, dissonances, and noises. Yet I couldn’t get it out of my head. Varèse said that he admired awkwardness in music, and now I see his point. The listener stumbles over it, shakes their head, pays attention; attention is a precious thing in music. Hank Shocklee, the producer behind the rap group Public Enemy’s iconic albums from the late eighties and early nineties, was another Varèse fan. He famously said that the group aspired to create the kind of sound world that musicians would hate. Another shout of “Poo!”

On the other hand, some of my favourite songs are quite pure and distilled: Dowland, Purcell, Mozart, Schubert have all crafted exquisite gems that sound effortless and just right. Yet their music also tells of pain and yearning—as do the blues, Reggae, soul, folk and pop songs. Perhaps these songs in their beauty are telling us that our anxieties and longings and disappointments are beautiful too—that we can accept and hold them as part of us, alongside our happier selves. It’s a path to becoming fully alive. Gardeners know that filth—manure, compost, worms—nourishes a vital garden.

And perhaps it’s neither filth nor purity alone, but the dialogue between them that feels more real, modeling the ambivalence and paradoxes we struggle with every day. The Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu said that music, like life, is about reconciliation. Music can embody how our polished, accommodating outer selves and our inner filthy, vital selves can live in harmony.

James Rolfe is a Toronto-based composer. His recent adventures in art song include the 2025 Juno-nominated recording of his song cycle Moths (words by André Alexis, with baritone Elliot Madore and pianist Steven Philcox, Canadian Art Song Project, Known to Dreamers, Centrediscs CMCCD 34224), and the CD Wound Turned To Light, a collection of songs to lyrics by Canadian poets (2023, Redshift TK540). Upcoming premiere recordings include O Greenest Branch with soprano Sara Schabas and conductor David Fallis, and Six Songs with tenor Colin Ainsworth, pianist Laura Loewen, and Pacific Opera Victoria. In the works is a cycle of songs to lyrics by poet Sophie Herxheimer.

Inside Ana Sokolović’s Love Songs by Kristin Hoff, mezzo-soprano

Love has always been and always will be the inexhaustible inspiration of human creativity. Love follows us everywhere; love is the cause and the result. Love evokes the strongest human emotions: love has led people to wars, but it has also inspired the most beautiful poems. All the languages sing about love the same way. Every happiness, worry, sadness and tenderness is similar to another.

– Ana Sokolović on Love Songs

With texts in one hundred languages, Love Songs encompasses fourteen vignettes that tell different stories of love. The piece demonstrates that no matter what our language, our time, our culture, or our upbringing, human feelings about love are universal. In a past interview I had with the composer, Ana described how the process of reducing so many feelings and angles of love down to so few poems was a very challenging one. To give an idea, the first reduced collection of texts contained fifty love poems, which the composer then categorized into a dramatic arc before reducing to the final count of thirteen poems.

While Love Songs doesn’t follow a traditional linear narrative, the piece traverses five larger themes. These include pure love, tender love, child’s love, mature love, and love for a person we lost, with poems in English, French, Serbian, Irish, and Latin. In addition to the main poems, the piece begins with a dove movement and most of the thematic sections also have a transitional dove interlude. These doves are where much of the linguistic fun happens, as they move through the words “I love you” in one hundred different languages. Aiming to respect tonic accents of languages within her musical structure, Ana crafted each dove to set up an atmosphere that prepares for the upcoming section. The doves offer energy and levity to contrast with the main poems and help to propel the piece forward, transitioning us into the character of the coming section. And why the name doves, you might ask? Well, Ana asks, what is the first thing we think about when we see a pair of doves?

The last section of the piece, love for a person we have lost, is the only section that isn’t preluded by a dove movement. Ana notes that this part of the piece is already so emotionally full that there is no space to say I love you anymore. Instead, it is the final poem of the previous mature love section that moves us into the tragic ending of the piece. Ana chose to leave this poem—“How do I love thee” by Elisabeth Barrett Browning— as a pure recitation, saying that no music could add anything to her words, which bring us so effectively from light and joy into the imagining of loss. Namely, the final line of the poem is:

…I love thee with the breath, Smiles, tears of all my life: and if God choose, I shall but love thee better after death.

The ensuing final section of loss incorporates two movements. The first features the text Ma morte vivante by Paul Éluard while the second sets two Latin Carmen poems by Gaius Valerius Catullus, which were written over two thousand years ago. In Ma morte vivante, the composer leaves space for the performer to decide the degree of interiority or exteriority through which to express their grief, offering an intertwining of crying, speaking and singing the words in an utterance that leaves us feeling like the pain is crawling up our skin. For the final movement, the Carmen poems are voiced by a boy at the tomb of his brother who was drowned and washed into the sea. Akin to the composer’s Balkan heritage (Ana is Serbian), here tradition requires him to publicly mourn his brother, to honour him at his funeral rites. But the young man can barely squeeze the sounds out of his anguished body, and just manages it before the piece culminates in a cycle of his gradually calming breathing.

And that is how Love Songs ends. After traveling through ecstatic joy, tender love for a child, joyful play, sensual desire, and deeply-rooted, mature love, the piece closes with a feeling of very deep sorrow. Having performed the piece many times now, I’ve had several audience members ask me why it ends in such tragedy. As Ana describes it, the piece culminates with a scream that connects us to the pure scream and birth of joy in the first poem of the piece, She. She goes on to say that just like there is a scream at the beginning of life, there is also a scream at the end of life. So while the piece may end in tragedy, because of the cyclic nature of life, we know that there will be another birth scream coming again soon. That is the unspoken hope we are left with as the piece comes to its painful close.

It is no small feat to learn Love Songs, just as it is no small feat to perform it. I took on the challenge in 2013 with support from the Quebec Arts Council (CALQ) and with guidance from the inspiring vocal artist and contemporary music specialist, Fides Krucker. A tour-de-force, the work truly was a beast to learn, taking several months to wrap my mouth and body around and another several months to memorize. That said, as with many very challenging artistic experiences, the reward for the work runs very deep. It is a rare privilege to stand alone on stage for forty-five minutes, moving fluidly through a rapid succession of characters, languages, and emotional states—each one a different facet of the shared human experience. The energy required is nothing short of immense, but the satisfaction is enormous. In the past twelve years, I have performed the piece a total of fourteen times in eight different cities, three provinces, and on two continents.

A Serbian-Canadian work, Love Songs has been performed in Canada, Slovenia, Croatia, Czech Republic, the USA, Holland and France. According to the composer, there are a total of eight singers who have learned and performed the entire solo piece, and four others who performed the voice/saxophone version. Additionally, the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence presented the work divided up for a collaboration of seven singers. Similarly, as part of Musique 3 Femmes’ activities, I coached musically a group of young singers for a 2021 production by the University of Ottawa School of Music, wherein the piece was divided up for eight singers and presented in an elegant and impactful (socially-distanced) staging by Anna Theodosakis.

So much is possible with Love Songs. When I asked Ana Sokolović what she likes particularly about this composition compared to her others, she said that what is special about this piece is that it is always a new and different story with each person who performs it. She speaks affectionately about the artists who have committed to learning the piece, remarking that the story is deeply affected by everything about who that performer is in the moment that they perform it. She says, love is abstract just like music is abstract. Scientists, poets and artists try to explain love, but they don’t succeed. We may never be able to put our thumb on love, but we can feel it, express it, live it, and we can definitely sing about it.

2025 winner of the Mécénat Musica Prix Goyer, mezzo Kristin Hoff has performed with Vancouver Opera, Tanglewood, Carnegie Hall, Met Chamber Ensemble, Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, Boston Pops, and Festival de Lanaudière, among others. Noted as a performer for her “appealing clarity and emotional heft” (New York Times), Kristin is also Artistic and General Director of Musique 3 Femmes, a Montreal-based contemporary opera company focused on new opera creation by women.

A Spirit Shaped by Song by Danika Lorèn, soprano & composer

Art song is not only a musical expression, but also an intellectual and philosophical one. Preparing to perform works of this depth requires more than technical skill; it demands reflection, interpretation, and a search for meaning that goes beyond the notes on the page. To embody a song is to step into dialogue with a poet, a composer, and centuries of ideas about love, mortality, nature, and the human spirit. In many ways it feels like my spirit has been shaped by song, since it has been a huge part of my life since I began taking voice lessons at age seven. From competing in every possible category year after year at my local music festivals, to creating and performing art song pastiche shows, it is safe to say that art song has greatly influenced my life as a performer. I suppose it is also no surprise that it now forms the backbone of my work as a composer.

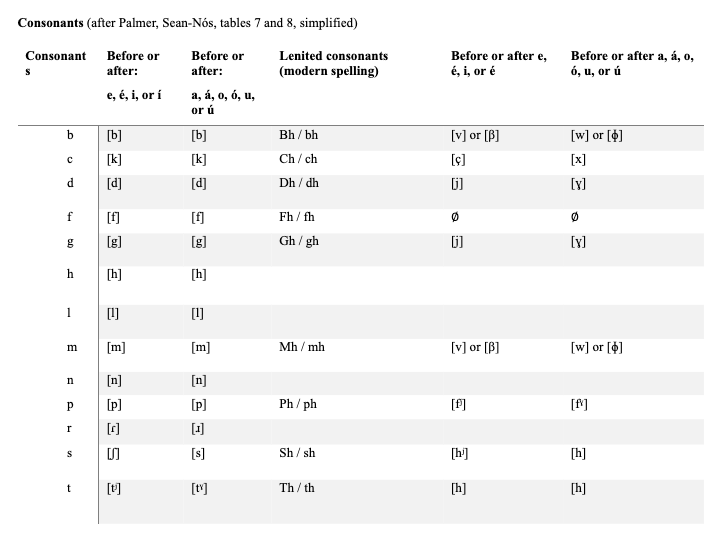

Eight years ago, I began to compose in a serious sense, and I put together my first album of 21 songs: First Fig Songbook. This songbook contains the earliest versions of my First Fig song cycle, which was my earliest full cycle. I began writing the cycle in 2016, but since self publishing in 2018, I have taken a note from Claude Debussy’s methodology and have allowed myself to edit these songs as I have grown. I haven’t made any major rewrites, but have made additions and refinements as I have lived with and performed the cycle. This has enabled the pieces to grow with me and also keeps me connected to a version of myself that was so precious and youthful!

When I first read Millay’s poetry, it was like I unlocked a voice inside myself that was ready to scream! Her writing in A Few Figs from Thistles is at once lyrical and unflinching, blending a sweet sentimentality with a sharp, modern candour that laid bare the intensity of my experience as a young woman in a big city trying to find her way. Millay’s title references the biblical proverb “Do men gather grapes of thorns, figs from thistles?” (Matthew 7:16). This proverb implies that one can’t expect good fruit from a bad tree, or good actions from a corrupt heart. Of course, Millay is being deliberately provocative, suggesting she can get something rich, sweet, and beautiful from that which appears to be barren or prickly. She is questioning completely the concept of sin as it has been projected onto womanhood throughout history.

The first piece of the most recent version of cycle is, perhaps confusingly, Second Fig. This short poem sets the tone for the cycle: ”Safe atop the solid rock the ugly houses stand / Come and see my shining castle built upon the sand”. Starting with this invites the listener to join the singer as we playfully dig into life’s muck and make something as beautiful and protective as a castle out of it. In the second song of the cycle, The Penitent, the poem begins with the dilemma of a “little sorrow, born of a little sin”, but by the end of the poem, Millay comes to a liberated conclusion: “if I can’t be sorry, why, I might as well be glad!”

From this liberation comes a fiery and fairly flippant rejection in the third song of the cycle: Thursday. This song is an ode to the beauty of learning how to say “no” instead of appeasing a needy lover. Thursday is written in a range where, in order to get clarity in the text, the voice can’t really be too tender or precious. It is bright and inviting but also a bit sharp. The piano part ends with a kind of “womp, womp” motif, with a few crunchy minor seconds to sound like a double bass that is losing its tuning, much as this lover has lost their lustre. I think of this song as one side of a coin, and the next song, The Philosopher as the other side of the coin. The vocal melodies begin nearly identically, though in different keys and with contrasting piano parts. And as dismissive as Thursday is (“And if I loved you Wednesday,/ Well what is that to you?/ I do not love you Thursday,/ So much is true”), The Philosopher is sweet and sincere, almost dumbstruck by the situation of an undeniable chemistry with an unexpected lover. The piano is mostly tender and sensual, but with a sharper, repeated-note motif to symbolize the nagging of that chemistry that is undeniable.

Midnight Oil is a more recent addition to the cycle, first released in my album MNSNGBK. Its original format is a round for four voices, but I have also written a vocal solo version. The harmonies in this round are quite crunchy and unpredictable, only coming together for a resolution in the final chord when all verses are sung/played together. It is a bit of a party anthem:

Sheet music and recording of Midnight Oil by Danika Lorèn, 2021 (recorded/mixed by Adam Harris)

Translation: I’ll sleep when I’m dead! Ah, youth. This is another moment where this song is one side of a coin and the following song, Grown-Up, is the other. Midnight Oil is a rebellious celebration of youth, and a willful ignoring of time’s control over us, whereas Grown-Up centres around the horrific notion of entering a phase of life where you prefer to go to bed…early (scream!). The fear of a domesticated adulthood was certainly something I related to when I wrote this cycle; now the performance on this piece is much more campy, over-the-top melodrama, and I have added a bloodcurdling scream to the final section (this is not written into any published version, but if you are performing these works and know the technique of screaming, feel free to let it rip!).

Grown-Up performed by Danika Lorèn and Stéphane Mayer, 2023 (recorded/mixed at Nobel Studios)

The next song of the cycle, Recuerdo is one of my favourites, and has been the star single of the cycle, having been performed around the world by many other singers. Most special to me was Georgia Burashko’s version (arranged for baroque ensemble) that toured around the Netherlands with Dutch Classical Talent in 2024. I also had the honour of recording the first version of the piece with Deutsche Grammophon after winning the DG prize in the Stella Maris competition.

Recuerdo performed by Danika Lorèn and Stéphane Mayer, 20 (recorded by Deutsche Grammophon)

The song was one of those that came to me in a fit of inspiration, immediately after reading the poem for the first time. It was also the first piece of the cycle that I wrote. It is the epitome of a youth-soaked love song. The tonal language of the song is vibrant and a rhythmic motif taken from the first line of text propels the song throughout. The language is not too flowery, just sincere and dripping with the energy of a first date that lasts until the next day. It is just one of those perfect poems:

I love this final stanza: it is morning now, the anticipation of the date has long left us, our lusty adrenaline has depleted, and we are nourished, keeping just what we need for now and paying the rest forward. The denouement of our love is fruit that we will pass along and nurture the rest of the world with. How sweet.

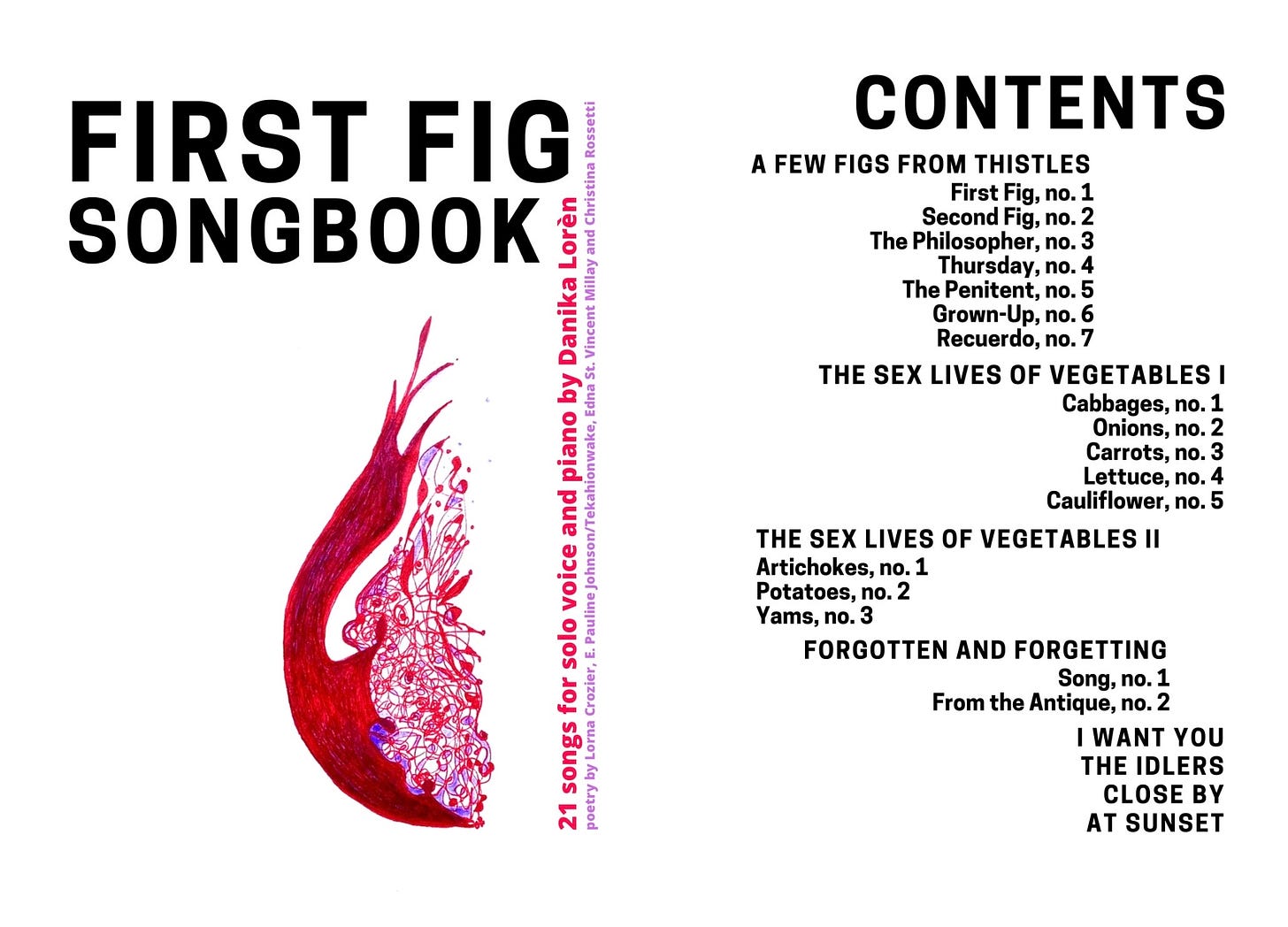

Finally, the cycle ends with the poem First Fig. One of my favourite “fun facts” about this poem is that it originated the metaphor of burning the candle at both ends, which essentially influenced the term being “burned out”. The wildness of youth and all of its paradigm shifting realizations have washed over us, and we are exhausted! Or should I say extinguished. This song holds a gentle grief in it. It isn’t a mourning over one’s death, but a mourning of youth once we turn the corner into adulthood. There’s no going back, no unburning of the candle. But, Millay doesn’t write this poem in despair! Rather, she addresses both friend and foe to reminiscence about what a very lovely youth it has been. Personally, I chose to take this reminiscing a step further, and now have a tattoo of my drawing of Millay’s double-ended candle on my forearm:

Thank you for spending this moment of reflection with me, and thanks to the Art Song Foundation of Canada for giving me this opportunity to share. I am really lucky that I have lived so much of my life through song, and that different versions of myself have been able to exist through these different versions of my work. The most recent version of First Fig is featured in my concert film UNBECOMING, along with two of my other song cycles: Tell Everyone and a new version of Sex Lives of Vegetables called SEX LoV 123. These three cycles are the works of my own that I have performed the most, and they feel like touchstones for my own artistic journey. Each one epitomizes an important pillar of self-growth, some philosophical cracking-open of my worldview, and together they form a kind of musical self portrait.

UNBECOMING will be available to watch online until September 9th, and you can find more information here, or purchase your pay-what-you-want access pass here. The film will be online until September 9th, and I will perform the first live public version of the show on November 15th in Waterloo with NUMUS (tickets here) with a guest appearance by the one and only Guy Few! Finally, for more information on my work past, present and future, feel free to visit DanikaLoren.com!

Danika Lorèn is a Toronto-based soprano and composer whose work blends classical tradition with contemporary innovation, earning acclaim for their expressive and theatrical performances. Their compositions have been showcased across Canada—by the CBC, Canadian Art Song Project, Canadian Opera Company, and more—and internationally at venues including National Sawdust, Muziekgebouw aan’t IJ, Leeds Lieder Festival, and Wigmore Hall.

Liza Lehmann’s Bird Songs by Marian Guay, soprano

Marion Guay, soprano, and Benjamin Kwong, pianist, performing Lehmann’s Bird Songs.

Version française

Née en 1862 et décédée en 1918 (curieusement, les mêmes dates que Claude Debussy), Liza Lehmann est une soprano et une compositrice anglaise. Elle entreprend une carrière de 10 ans en tant que chanteuse interprète en 1885 qui prendra fin en 1894 lorsque qu’elle se marie au compositeur et artiste Herbert Bedford. Elle se concentrera dorénavant sur la composition de pièces vocales qui connaitront un franc succès au cours de sa vie.

Lehmann sera surtout connue pour ses cycles de chansons, souvent à caractères charmants, humoristiques et parfois mélancoliques, notamment In a Persian Garden, The Daisy Chain et Bird Songs. Ce dernier a été composé en 1907 sur des paroles apparemment écrite par Alice Sayers, la nourrice de la famille Bedford. Chaque pièce de ce cycle à le nom d’un oiseau faisant parti du paysage sonore et champêtre britannique. Lehmann nous transmet ainsi ses souvenirs de temps heureux dans la campagne anglaise.

English version

Liza Lehmann, a soprano and English composer, lived from 1862 to 1918 (curiously, the same dates as Claude Debussy). She undertook a ten-year singing career beginning in 1885 which ended when she married the composer and artist Herbert Bedford in 1894. From then on, she concentrated on composing vocal pieces which achieved great renown during her lifetime.

Lehmann is best known for her song cycles which contain a charming, humorous, and at times melancholic character, notably In a Persian Garden, The Daisy Chain, and Bird Songs. The latter, composed in 1907, is set to texts apparently written by Alice Sayers, the Bedford family’s nursemaid. Each piece in this cycle is named after a bird that forms part of the British rural soundscape. Through these lovely pieces, Lehmann conveys her joyful memories of her time spent in the English countryside.

Marian Guay is a versatile soprano based in Montreal. She holds a bachelor’s degree in classical voice from McGill University’s Schulich School of Music, and is currently pursuing her master’s studies at the Conservatoire de musique de Montréal. She also teaches voice at the École de musique Vincent-D’Indy of Montreal.

Editor’s note: Readers, do you have a little known song cycle you’d like to share with the Art Song Canada community? Write to us at [email protected] to be featured!

Allan, Jennifer Lucy. “‘The perfect accompaniment to life’: why is a 12th-century nun the hottest name in experimental music?”. The Guardian, 15 July 2025.

Please consider making a contribution to the Foundation today.

As Canadian pride has swept across our vast nation in recent months, we thought it only fitting to delve into a bit of Canadian art song history for this month’s edition. In it, three experts offer insights into works by three important Canadian composers of the 20th century (stay tuned for our 21st-century edition!). Baritone and recent doctoral graduate of the University of Toronto Bradley Christensen ellucidates some of the final conversations he had with the great Canadian composer of many wonderful art songs, John Beckwith (1927-2022). Mezzo-soprano and professor Tina Alexander-Luna from the University of Regina takes us into the world of Violet Archer (1913-2000). Finally, the composer and recent author of Between Composers: The Letters of Norma Beecroft and Harry Somers (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2024) Brian Cherney offers us a detailed look at the songs of Harry Somers (1925-1999) – a resource we believe will prove useful to all singers and pianists interested in performing or studying these works!

Once you’ve finished reading all of that (it might take you a bit!), keep scrolling to read our “Introducing…” column by the Newfoundland-born, Germany-based composer James Hurley, who introduces us to his Great Irish Poets Songbook.

As always, we hope this issue inspires you and reminds you of the transcendent power of art song. If you enjoy this issue, please consider donating to support the Art Song Foundation of Canada’s bursary programs for young Canadian singers and pianists.

— Sara Schabas, editor

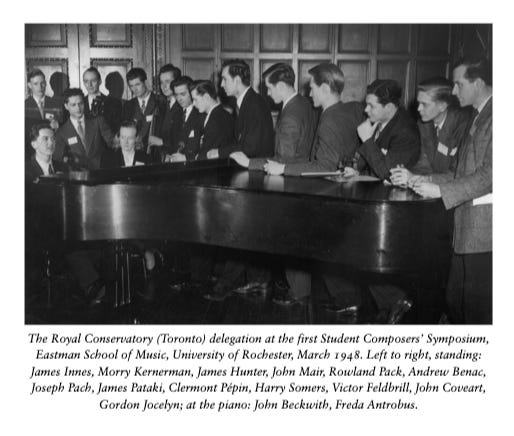

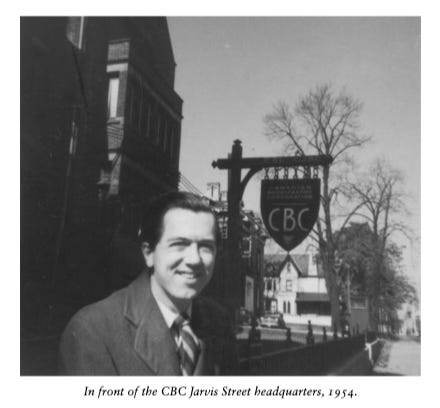

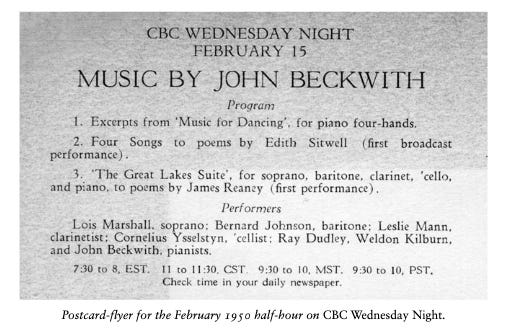

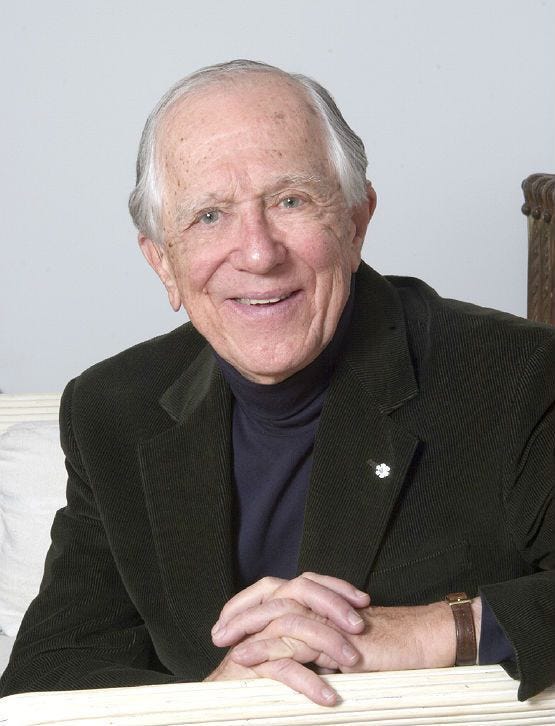

John Beckwith: A life of song by Bradley Christensen, baritone

Born March 9, 1927, in Victoria, BC, John Beckwith was a composer, musicologist, teacher, and author whose significant contributions to the Canadian art song canon, and in fact, the broader Canadian artistic landscape, spanned a remarkable seven decades. Beckwith wrote over 150 compositions, including four operas, a dozen orchestral works, chamber and solo works, songs, works for chorus, and approximately 200 arrangements of Canadian folk music. The song repertoire of John Beckwith spans an incredible 67 years, with much of his output utilizing the literature of important Canadian literary figures, including bpNichol, Margaret Laurence, Colleen Thibaudeau, and Miriam Waddington. Beckwith also turned to the sounds of the people and regions for inspiration, whether it be a song composition speaking of winter in Winnipeg (“The Snow Tramp,” Three Songs to Poems by Miriam Waddington, 2003), or the setting of a Newfoundland folk song (The St. John’s Girl, 1969). In setting the texts, Beckwith recognized the need for specificity, and rather than attempting to channel a generic Canadian soundscape, he attempted to focus on the identity of specific regions. In his book Unheard of: Memoirs of a Canadian Composer, he wrote, “It’s fruitful, I’ve found, to ask the question, ‘What are the local or regional sounds, gestures, expressions, that would be appropriate to this compositional assignment?’” (200)

I am honoured to have been asked by Art Song Canada to write about John and his contributions to the Canadian art song canon. I interviewed John between September 2020 and September 2022 for over 16 hours as part of my research for my 2023 doctoral dissertation titled “The Repertoire of John Beckwith for Solo Voice and Piano: An Interpretive and Pedagogical Guide.” John was incredibly generous with his time, and I shall forever remember those interviews. He was sharp, remembering events from 70 years prior, and the humour that he portrayed in various song compositions was clearly an extension of his own personality. When I asked him questions such as, “Is there a reason that most of your songs don’t use a key signature?” his response was: “You can’t expect a singer to be governed by a tonality.” I laughed (although I wasn’t entirely sure that was a joke) before John clarified that he didn’t like to use a key signature because he found it restrictive. OK, he was joking! ☺

One significant observation that came from these interviews was discovering how well-read Beckwith was. It made sense upon learning that in his first year at university, he enrolled in an English literature course. His love of reading and his passion for the English language is demonstrated in his song catalogue, not only by the wide range of authors whose texts he sets, but also by the eclecticism in his taste.

Beckwith’s regard for literature and poetry made him a strong story-teller. He was always preoccupied with text, the sonority of syllables, and getting the literary background across to the audience. When I asked him what his most common suggestion for singers and pianists was, he said for singers, “stress the words,” and for pianists, “go with what the singer is trying to get across.”

Generally speaking, Beckwith’s songs are challenging to perform. Beckwith was exact in his writing (rhythms, articulation, etc.); his compositions are concise and economical. A successful performance of a Beckwith song combines the precision of small detailed work with the presentation of larger gestures. The songs may take a while to learn, but the precision of the learning is to find freedom in the performance. Soprano Monica Whicher, for whom Beckwith wrote the cycle Stacey (1997), explained to me in an interview that because John’s music is so detailed, it is impossible to extricate these details from the context of the whole, yet one can never relinquish the over-arching gesture and emotion in the midst of this detailed work.

I have to say, prior to my doctoral recital, when I took his songs to him for coaching, I was quite nervous, as I expected him to pull me up on all the little details that may or may not have been included. However, while he offered a couple of suggestions regarding emphasis of particular words or messages he wanted conveyed, he simply seemed grateful and excited that his works were being performed. This feeling of gratitude I often observed in his recounting of past events.

There is much to be discovered in the rich tapestry of the Beckwith song catalogue. He is a unique voice in the canon of Canadian music, and, as Monica Whicher explained, is someone who devoted an entire life to the exploration of poetry and their own style. John passed away on December 5th, 2022 in Toronto at the age of 95, leaving behind a catalogue reflecting major themes of his life and work.

Award-winning baritone, voice teacher, and guest clinician, Dr. Bradley Christensen enjoys a busy multi-faceted career in the arts. Bradley obtained his Doctorate from the University of Toronto; he is an alumnus of the prestigious Rebanks Family Fellowship and International Performance Residency Program; and he furthered his artistic development as a young artist with Opera on the Avalon, Highlands Opera Studio, and Opera North.

The Art Songs of Violet Archer by Tina Alexander-Luna, mezzo-soprano

A once-household name, Canadian composer, Violet Archer, passed away in 2000, and this year marks 25 years since her passing. In a CBC interview, Archer was coined as “Violent Violet” known for the difficulty level of her writing and her neo-classical stylistic influences from composers like Béla Bartók and Paul Hindemith. Born in 1913 in Montreal to parents who were new immigrants to Canada from Italy, Archer had exposure to music at a young age and began studying piano formally at the age of nine. In a 1998 interview with Barbara Harbach, Archer speaks about her early interactions with music stating, “as an infant the sound of the piano cast a spell over me. The sound of a violin made me cry. The piano drew me to music.”

Despite being discouraged to study music at the University level by her family, Archer completed her Bachelor of Music in Composition at McGill University in 1936. In the early 1940’s, Archer would travel to New York City to study with well-known Hungarian composer, Béla Bartók, and by 1942, Archer had already composed thirty-eight known works for orchestra, solo voice, choir, and chamber groups. Archer completed her master’s degree at Yale University in 1949 and worked with composer Paul Hindemith. Although she travelled and taught as sessional faculty at several universities in the United States, it was in 1962 that Archer began her tenure at the University of Alberta developing their theory and composition programs. The bulk of her compositional output was during her time in Edmonton, and despite being far from family, she flourished in her compositional work, personal life, and in her advocacy for the performance and study of new Canadian music. Although she retired from the University of Alberta in 1978, Archer remained in Edmonton until 1998 when she moved to Ottawa to be closer to family before passing away in 2000.

During a career that spanned over six decades, Archer composed just over 300 pieces including works for orchestra, chamber ensembles, solo piano, voice, choirs, and many diverse instrument combinations. According to a 2006 article by musicologist, Linda Hartig, Archer was, “serious about writing for beginning and intermediate students as well as for sophisticated performers,” and this is certainly exhibited in her compositional works for voice and piano. Although not known specifically for her contributions to art song, Archer wrote an array of interesting and viable compositions for voice and piano that can be interesting choices for singers and teachers! Archer wrote 110 songs for voice and piano and of these, about 70 are either written for mezzo-soprano voice/medium voice or are suitable for it. This is a large portion of her total compositional output that has been overlooked, underperformed, and underrepresented. Archer’s songs frequented texts by Canadian poets and there were also folksong influences in her writing.

To be fully candid, even as a singer educated entirely in Canada, I had never learned any of Violet Archer’s songs until I began researching her during my doctoral studies at the University of Toronto. I felt oddly drawn to her because of her tenacity, how she was from the east (Montreal, and I am from Ottawa), and spent the bulk of her music career in Western Canada (where I have spent most of my professional career). Archer was also known for how she loved her cats- and who doesn’t love cats?!

So, here we are twenty-five years after her death, and access to the art songs of this prolific composer is only slightly easier than 25 years ago. Here’s hoping we continue to see more Canadian works for voice published and made more accessible to our Canadian voice community!

Mezzo-soprano, Tina Alexander-Luna, is a performer, teaching artist, and is Assistant Professor of Voice at the University of Regina. She recently completed her Doctor of Musical Arts from the University of Toronto. She performs frequently in recital and concert settings and will be presenting a lecture-recital in July of 2025 in Toronto at the International Congress of Voice Teachers (ICVT) entitled “Canadian Frontiers: the art song contributions of Canadian composer Violet Archer.”

The Art Songs of Harry Somers (1925-1999): A brief survey by Brian Cherney

Strictly speaking, the art songs of Harry Somers span the entire length of his creative life. His earliest song, “Stillness,” was written in January 1942 when he was seventeen, only about three years after he began taking piano lessons. His last song, “Eternity,” was a very brief setting of a four-line poem of that name by William Blake, written shortly before his death in 1999. Another song, also using a brief poem of Blake, was planned but not written. Since by that time Somers was very ill, the song may or may not have been left as it was had he had more time to work on it. During the later 1940s and early 1950s, he produced a small number of conventional songs for voice and piano (including several sets) but in the 1960s he began to move away from his hitherto traditional use of the voice, culminating in more experimental works in the early 1970s, such as Voiceplay (for solo voice) and Kyrie (for solo voice, choir, and instruments). These are definitely not art songs. Later works for voice and piano include such pieces as the fourteen-minute-long operatic scene Love-In-Idleness (1976), with a text taken from Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. The sheer length of this piece excludes it from the art song category, whereas Shaman’s Song, for voice and prepared piano (1983), will be considered here. Although this piece is somewhat lengthy in terms of traditional songs, it is likely to be heard as a single, highly unified piece, not as a series of episodes. The particular use of the voice and its materials as well as the unusual nature of the piano accompaniment provide a consistent sound colour and atmosphere throughout. One could argue that it is a kind of extended and very intense art song—a stretched-out, magnified, and modified version of a traditional Lied, perhaps?

His earliest song, “Stillness,” was a setting of his own poem and was the first of his pieces, written in the 1940s (culminating in North Country for string orchestra in 1948), which were influenced by the landscape north-eastern Ontario, particularly the area of Temagami, which he had visited as a child with his parents:

This poetic depiction of the special qualities of the night (so dear to Romantic poets and musicians) no doubt sprang from the same fascination with the nocturnal world as had impelled Somers to wander the streets at night as a young child. (His correspondence and hastily jotted-down memoranda over the years are full of descriptions of night—the sounds, the light, etc.) In the 1950s the nocturnal world reappeared in the Five Songs for Dark Voice (“At four o’clock, before the dawn/ In the echoing street, there is yourself.”), although he himself did not write the text for these songs.

Some of the harmonic language of “Stillness” is based on stacked fifths in the left hand against fourths in the right, the latter a whole tone higher. This sounds like a thirteenth chord or a ninth chord with an added sixth. Chords often move in parallel motion, by semitone or whole tone in various voices. This is type of harmonic activity is typical of his other early music. The poem’s structure is faithfully reflected in the textural changes in the music, with the first verse basically melody with chordal accompaniment. The breeze in the second verse is represented in flowing arpeggio figures which, like certain of the harmonies, recall Debussy, especially because elements of the arpeggio are used to suggest a hidden melodic voice as a counterpoint to the voice line. In the third stanza the piano slows up into rising quarter-note arpeggios, again built on fifths (L.H.) and fourths (R.H.) moving in parallel motion; again, the harmony suggests major seventh or ninth chords. The last stanza reintroduces the harmony and texture of the opening and the “one soft note of stillness” appears as the pitch B-natural, which had appeared near the opening as the top note of the main reference harmony: A-E-B-C-sharp-F-sharp-B. The setting is syllabic throughout and the voice writing rather angular in places but generally unremarkable. There is nothing in Somers’s correspondence or other papers to indicate that the song was ever performed.

His first set of songs, entitled simply “Three Songs,” was commissioned by the Forest Hill Community Centre in Toronto, and written over a period of six months, beginning in January 1946. These were first performed by soprano Frances James, who performed much contemporary Canadian music in those years. All three poems are by Walt Whitman. It may be that Somers became interested in Whitman through his mother Ruth’s involvement with the Toronto Theosophical Society—Whitman was a figure greatly admired by the theosophists as far back as the 1890s. Whatever the impetus, all three poems depict nighttime. In “Look Down Fair Moon” the moon looks down upon the dead of the Civil War. “After the Dazzle of Day” depicts the stars which emerge in darkness, as well as the silence of the night, and the third song, “A Clear Midnight,” merges several previously depicted qualities of night that the soul can embrace and loves “best,” such as silence and stars but also sleep and death, as if the night sky offers the soul, a window to eternity. In these settings, the piano writing is more economical than in “Stillness” but still largely uses either chordal writing or arpeggiated figures, the latter either very short (suggesting the moon looking down) or very ornate and extended, as in the piano introduction to “After the Dazzle of Day” (to portray the “dazzle” of daylight). But the piano setting of the third song is the most effective, with its clear texture and motivic materials. A steady eighth-note semitone figure (A-sharp—B) above repeating octave E’s creates clarity but also suspense and is followed by an arpeggiated rhythmic figure, continuously repeated against the slow-moving voice part. This sequence is stated twice, thus providing a clear formal structure for the song (ABAB). The writing for the voice in these songs is expressive and less angular than in “Stillness” but still syllabic and rather careful, with brief melodic figures, repeated-note declamation of certain phrases, and the avoidance of sudden contrasts of register—in fact, the range of the voice part is confined to the staff. It’s interesting to note that the repeated-note declamation used early on recurs in his mature vocal writing, but the repetitions are more drawn out and intensified by the addition of a grace-note figure before each repeated note (see the first song in Evocations, for instance). In general, it seems as though he was, at this time and over the next few years, much more comfortable writing for the piano (his own instrument) than for the voice.

Those familiar with Somers’s juxtaposition of tonal and atonal passages in much of his music of the 1950s, will not be surprised to find examples of this in these early songs. “Look Down Fair Moon” begins with a rather dissonant piano introduction consisting of brief linear figures and dissonant chords (lower in register) but this all “resolves” to a plain d-minor chord when the voice enters—probably a way of contrasting the purity and beauty of the moon with the ghastly scene of bodies still lying on a battlefield many hours after they were killed. This juxtaposition is carried through to the final bars, again probably to underline the different images portrayed. Yet the song ends on a dissonant chord in the high register. There is no harmonic “resolution” of the scene depicted. On the other hand, “After the Dazzle of Day” concludes with a rising arpeggio figure built in fifths and fourths on C-sharp, suggesting in sound the last two words of the text— “symphony true.”

The title page of the original manuscript of “Three Songs” contains the following note: “with a fourth song which may or may not be included.” It may well be that this fourth song was never included in performances, since even on the Centrediscs recording of Somers’s songs (Songs from the Heart of Somers), this song is not included and there appears to be no recording of it. The title of the song is “A Song of Joys” and it is also a setting of Whitman, this time the first three verses of Whitman’s lengthy poem of that name. The song was written in 1947, and Somers entered it (as well as his Piano Sonata No. 1 [“Testament of Youth”]) in the Arts Competitions at the 1948 Summer Olympics in London. Neither piece won a medal (but John Weinzweig’s Divertimento No. 1 for flute and strings won a silver medal). The text (beginning “O to make the most jubilant song!”) is preceded by a substantial piano introduction which sets the mood, with its ¾ rhythm, fast tempo (marked “Allegro vivace, full of life, brimming over”) and homophonic texture. All of this gives the song the character of a fast, impetuous dance. The piano chords are, again, often built in fourths and fifths moving in parallel motion and these intervals are also prevalent in the voice part. In this song, the range of the voice part is somewhat more expansive than in the previous songs in the set, and its highest note, a G-flat 5, is saved until the very end, making the voice part even more effective and concluding the song with a sense of triumph.

In 1947 Somers wrote a single song, entitled A Bunch of Rowan, with a text by Diana Skala. Skala was not only a poet whose work had appeared in the periodical Saturday Night but had, evidently, studied piano and composition at the Toronto Conservatory of Music during the early 1930s, according to a short memoir she wrote years later (“A Letter from Sir Charles G.D. Roberts [A Personal Memoir],” published in Studies in Canadian Literature XI, no.2 [1986]). The “rowan” of the title refers to the rowan tree which, in some cultures, is thought to give protection from malevolent persons and/or witches. In the poem, the narrator, who seems to have led a life of excessive pleasure, asks to be laid to rest “where the willows are listening… with a bunch of rowan upon my breast” since she (or he?) does not know “evil from good.” The musical setting of this doleful, three-stanza poem, with its slow, steady tempo, has the quality of a dirge, with rolled chords in one or both hands of the piano which proceed in even, slow quarter notes in the actual accompaniment of the text. These rolled chords suggest the strumming of a string instrument and the frequent d-minor harmony, with chromatic slides to more dissonant chords or simply to a contrasting triad, suggest that Somers intended this setting to evoke the sense of a bard or minstrel singing of the deeds of a hero (or heroine?). The triadic arpeggiation in the voice part tends to support this impression. On the other hand, a short piano introduction consists of a high melodic voice which adds strong dissonances to the underlying d-minor harmony. This introduction returns in more or less the same way between each stanza, while each stanza is set to essentially the same music; thus, the setting is strophic (which also supports the idea of a song performed by a bard). It may be that Somers intended the tonal music to represent the “good” and the dissonant chords (many of which are ninth chords on G-flat) to represent “evil,” which the narrator cannot distinguish between (“For I know not evil from good.”). A Bunch of Rowan was performed in the summer of 1949 in Budapest during the second World Festival of Youth and Students.

Somers’s next set of songs, entitled Three Simple Songs, was written in 1953 and two of the songs were first performed 20 November 1954 at a Canadian League of Composers concert in Hamilton, Ontario by mezzo-soprano Trudy Carlyle and Mario Bernardi. The texts of the songs (“The Garden,” “Asleep,” and “My Faith Move Mountains”) were written by the Toronto lawyer and poet Michael Fram (1923-1989), who wrote the texts for no fewer than six works of Somers between 1953 and 1956, including two important works of those years: the one-act opera The Fool (1953) and the orchestral cycle Five Songs for Dark Voice (1956), the latter premiered by Maureen Forrester at the 1956 Stratford Festival. Fram was actually practicing law during these years but was also a serious poet who had met Somers through the latter’s first wife, Catherine Mackie.

The texts of Three Simple Songs are far more complex and enigmatic than the texts of the previous settings. The first two songs, “The Garden,” “Asleep,” both depict young children, first at play, then asleep, and in both there is a sense that the parent who is surveying the children wants to protect them from the world of adult emotions (“futile laugh,” “infected anger”) or, as in “Asleep,” prevent anything from interrupting their sleep. (Fram and his wife were the parents of young children during these years.) The piano accompaniments of these two poems are far thinner and more linear than in the Whitman songs. It looks as though a twelve-tone row was used to some extent in the first song but not systematically, since there are also scale-like figures, chords built in fourths and fifths, but there are again here unexpected juxtapositions of atonal and tonal pitch structures. This is especially true in the second song, in which the middle section is like the recitative format of some eighteenth-century opera, with e-minor and d-minor rolled chords providing the harmonic underpinning of each short phrase in the voice. The piano parts of the outer sections, however, are dissonant, whether the texture is chordal or linear. The voice part in these songs is generally more angular, disjunct, and wider in range than in the Whitman songs, yet still essentially lyrical.