Issue 27 – March 2025

A winter journey

Fremd bin ich eingezogen,

A stranger I arrived here,

Fremd zieh’ ich wieder aus.

a stranger I go hence.

Der Mai war mir gewogen

Maytime was good to me

Mit manchem Blumenstrauß.

with many a bunch of flowers.

Das Mädchen sprach von Liebe,

The girl spoke of love,

Die Mutter gar von Eh’, –

her mother even of marriage.

Nun ist die Welt so trübe,

Now the world is dismal,

Der Weg gehüllt in Schnee.

the path veiled in snow.

- Willhelm Müller (English translation by William Mann)

While it may be March, Canadians know winter is far from over. Indeed, as the end of our annual winter journey begins to enter our vision, we at Art Song Canada thought exploring Franz Schubert’s eponymous song cycle—deemed by some as the world’s first and greatest of concept albums—might be the perfect way to end the season. In the words of the great Lieder singer Ian Bostridge: “For the initiate, Winter Journey is one of the great feasts of the musical calendar: an austere one, but almost guaranteed to touch the ineffable as well as the heart.”

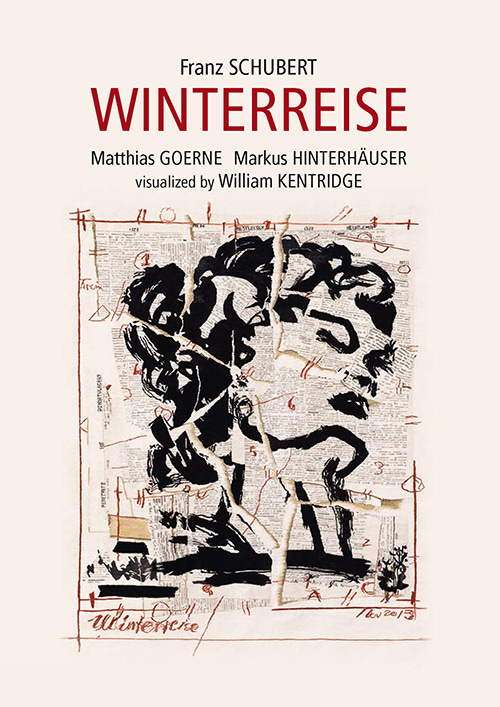

Our winter journeytakes us around the globe with three personal accounts from artists intimately familiar with Schubert’s opus. We begin in Waterloo, Ontario, where the prolific Canadian bass-baritone Daniel Lichti first discovered Winterreise, before he became one of the world’s most prolific interpreters of the cycle. We then venture to Berlin, the base of the British-Canadian soprano and pianist Rachel Fenlon, who has made a name for herself internationally by singing and playing the work simultaneously. Finally, we stop by Johannesburg, where the South African artist, filmmaker, and opera director William Kentridge—who created a visual Winterreise for Matthias Goerne, Markus Hinterhäuser and the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence—listened to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Gerald Moore’s Winterreise with his father on Sunday afternoons after lunch.

As always, we hope this issue inspires you and reminds you of the transcendent power of art song. If you enjoy this issue, please consider donating to support the Art Song Foundation of Canada’s bursary programs for young Canadian singers and pianists.

— Sara Schabas, editor

My journey with Winterreise and my companions along the way by Daniel Lichti

In the summer of 1971, I heard Winterreise for the first time.

It was performed in the Theatre Auditorium, at what was then known as Waterloo Lutheran University, now Wilfrid Laurier University – an auditorium where basketball games were more the norm than a Sunday afternoon Schubert recital. I will never forget it, or its effect on me.

I was too much of a newcomer to understand the unmistakable attraction I felt to explore this kind of artistic expression and this great song cycle, but I felt it intensely. The pursuit of learning it, studying it, memorizing it, and engaging with many partners in its performance in many settings throughout my now 50 years of professional life has contributed immensely, more than any other single influence, to my growth as an artist. The initial impression was one of awe – that a narrative communicated through the singer and a pianist could stimulate my imagination so powerfully at first exposure was new to me. It wasn’t just the text (that came later with fluency), but the combination of the journey narrative and the compelling musical partnership between singer and pianist that drew me in, and set me off on my own journey with Winterreise.

The performance in 1971 was given by Canadian baritone, David Falk, and German pianist, baritone and voice pedagogue, Theo Lindenbaum. These men are both gone, but each influenced me in significant ways. David, along with my first voice teacher, Victor Martens, both of whom were foundational in building a highly respected Voice and Opera program in a fledgling Faculty of Music at WLU, continued to support and mentor me when I was invited to join the Faculty of Music in 1998. Theo became my teacher and mentor for three years at the Nordwestdeutsches Musikakademie in Detmold, Germany. Martens and Lindenbaum were both involved in my learning process – I sang the first seven songs of the cycle on my final recital as an undergrad at WLU and then continued to work my way through the rest of the cycle in my Detmold days, managing a full performance in the spring of 1977 with a fellow student pianist for an audience of seniors in the nearby Spa-town of Bad Salzuflen. I was pretty sure my audience knew the work better than I did.

Not long after returning to Canada to work at building a professional profile in earnest, I met Leslie De’Ath, Professor of Piano and Collaborative Piano at WLU, and likely one of the most active musicians in the Kitchener-Waterloo region throughout his illustrious career. I have always thought of him as an artist-intellectual, and appreciate his influence on me through our many performances of Winterreise, our conversations, and through his writing. We have performed in traditional recital settings, but also at a 50th wedding anniversary celebration in a private home, and in the Rotunda of the National Gallery in Washington D.C., where we filled in at last minute for an ailing Hermann Prey at a concert commemorating the Millenium of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Leslie and I also recordedWinterreise for ANALEKTA, distinctive because of the use of a 1851 Streicher fortepiano, which has a sound perhaps akin to that with which Schubert and his contemporaries were familiar.

Along the way, I encountered the NYC-based collaborative pianist and educator, Arlene Shrut, and at our first rehearsal for an unrelated audition, realized that we communicated easily and deeply with Lieder, and for a few years we worked together several times, including a performance of Winterreise in Syracuse, NY. It was with her that I then sang my first recitals at the National Gallery in D.C., and we partnered on the first digital recording of Lieder by Dorian Recordings.

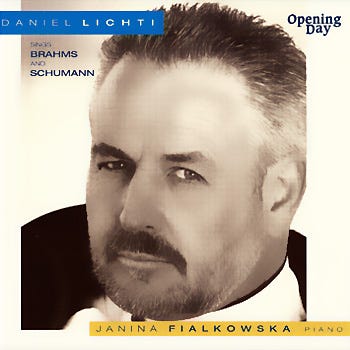

In the early ‘90s, fate brought me together with the renowned Canadian pianist, Janina Fialkowska at the Carmel Bach Festival in Carmel by the Sea, CA. Before long we were giving recitals around Ontario that turned into recordings for Opening Day, Schubert’s Schwanengesang, and songs of Brahms and Schumann. Our Winterreise adventure took place in Ottawa at Festival Canada, organized by the late Nicholas Goldschmidt – our page turner that evening was Janina’s good friend, Angela Hewitt!

Further performances of Winterreise have included the Teatro Manoel in Italy with pianist Michael Laus, the Temple Square Recital series in Salt Lake City with pianist Paul Dorgan, in the former homes of artists and thespians in Saint Petersburg, Russia with Irina Chukovskaya, in Quebec City with Leslie De’Ath, tours from Winnipeg to Victoria with Sandra Mogenson, with Roland Pröll in Germany, Laetitia Bougnol in Lyon and Paris and most recently, Kitchener to celebrate my 50th year of professional life, a house concert in Kfar Vradim, Israel and recitals in Waterloo and Toronto with the Israeli pianist Ephraim Laor, and recently, an arrangement of the cycle by cellist Richard Krug, which I have performed with the Penderecki String Quartet. While Laetitia Bougnol was in Kitchener in July, we took six young pianists and six young singers with us on a deep dive into Winterreise, as the focal point of the inaugural Art of Lied festival and workshop.

All of the pianists with whom I have partnered have enriched and influenced me as an artist in distinct and special ways. Each has brought their personality, artistry, imagination, and their individual history of influences to bear on our musical relationship, with a generosity that has been humbling and instructive.

The winter journey continues.

Acclaimed as one of Canada’s finest concert and oratorio singers, bass-baritone Daniel Lichti continues to perform worldwide. Since beginning his career at the 1974 Stratford Festival, he has bowed with the Canadian Opera Company, Landestheater Detmold, at Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, L’Opéra de Montréal, Opéra de Québec, Opera Atelier, Edmonton Opera, Opera Hamilton, the BBC Proms, the Bach Choir of Bethlehem, the Bachakademie Stuttgart, the Thomaskirche in Leipzig, Usher Hall in Edinburgh, at St. Albans Organ Festival, the Hercules Saal in Munich as well as at the Kennedy Center and Carnegie Hall. From 1998–2017 Lichti was Associate Professor and Coordinator of Voice for the Faculty of Music at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

Schubert and Me by Rachel Fenlon, soprano and pianist

Schubert’s Winterreise is a work that has lived with me as a companion, a mirror, and a vessel for the past four years. I’ve toured the world with it, recorded it, and lived through profound personal moments alongside it. My artistic life feels like it falls into two categories: life before Winterreise and life after. Having performed it over 20 times as a self-accompanied singer/pianist, I feel I am only beginning to scratch the surface of what Winterreise has to say —and what it has given me.

When Schubert composed Winterreise in 1827, he was already living with the terminal stages of syphilis, dying the following year. What he left behind in this cycle feels like an unraveling of his own grief. The protagonist embarks on a cold, dark journey through winter toward a place “no one has ever returned from.” Winterreise grapples with the darker, more isolating aspects of humanity—grief, loss, unrequited love, and longing. Yet even amid this overwhelming darkness, Schubert offers a surprising amount of light.

“For long years I felt torn between the greatest grief and the greatest love… Whenever I attempted to sing of love, it turned to pain. And again, when I tried to sing of pain, it turned to love. Thus were love and pain divided in me.”

—Franz Schubert

This quote feels like a glimpse into Schubert’s soul, and it echoes throughout Winterreise. Even in its most sorrowful moments, the music in Winterreise often shifts between contrasting emotional states. In songs that might be considered the “saddest,” such as Die Nebensonnen and Das Wirtshaus, we encounter major keys that feel unexpectedly serene. In songs like Wasserflut, set in the key of e minor, there is a sense of lightness and the calming cyclical nature of water. In Die Post, we get a burst of energy and an unexpected hope. In Der Leiermann, often perceived as chilling, there is an acceptance of life’s cyclical nature in the open fifths that ring throughout. Schubert’s contrasting emotional landscapes in Winterreise—joy and sorrow, love and loss—reveal an intimate look into both the psyche of his protagonist and his own.

I first opened the score of Winterreise in 2021. That year, during the pandemic, was a time of collective grief, but also a time of personal loss. One of my closest childhood friends, Karyn, was diagnosed with terminal cancer. I began to immerse myself in the music, knowing that I would lose her. A witness to her illness, Schubert was a companion to my grief. Karyn passed away in 2023, as I was touring Winterreise and recording it. Looking back, it’s unimaginable that I went from attending her celebration of life to the recording studio in the same week. My Winterreise feels deeply interwoven with my own grief, and it has shaped so much of how that grief has been embodied and shared on stage.

In German, there’s a word, Innigkeit, which translates to “intimacy, tenderness.” Unlike Intimität (also meaning intimacy), Innigkeit refers to a genuine, honest intimacy meant to be shared. Schubert, above any other composer, opens his soul with intimacy that invites us to share in his joy and sorrow. In this communion, we feel our own. In Winterreise, the protagonist invites us into a deeply personal world. While metaphors and symbolism abound, there is a clear specificity and intimacy in the narrative. For example, the devastating first word, “Fremd,” meaning “stranger” (“A stranger I arrived, and a stranger I shall depart”).

We’re given everything—from the passing of time to the landscape and surroundings, and in the music, our emotional landscape—all to pull us into the protagonist’s reality.

As an interpreter, our work is about making sense of someone else’s world. Being both singer and pianist for Winterreise, this work has felt solitary, and intensely personal. There are several things I’ve learned so far on my Winterreise journey. First, being both a singer and pianist is innately solitary, so lean into that sense of loneliness, lean into the question marks. Second, there is only truth or not truth with Schubert—no in-between. If I can’t access my own deep emotions through what Schubert has written, it won’t resonate with the audience. Third, the magic of Winterreise comes alive on stage. You must live the journey with your audience to truly convey it. Winterreise must be as much about the silences between the music as the music itself. A close friend, Simon Bode, a celebrated German tenor, called me after my third performance in 2022 and said, “Congratulations, now you begin to really understand it!” Finally, performing Winterreise repeatedly requires constant reinvention. A key word for me in performance is “surrender,” a mantra I repeat before I go on stage. But surrender is constantly renegotiated. It’s the same with understanding Winterreise. Different pieces reveal themselves on different nights, and much of it is about being open enough – in your mind, in your heart – to receive different perspectives in the moment.

I heard an interview with Judi Dench, speaking about her role as Cleopatra:

“We did a hundred performances (of Antony and Cleopatra). I knew that there was a laugh in a line that Cleopatra said. I tried for 99 performances to get the laugh, and on the hundredth, I got the laugh.”

—Judi Dench

Winterreise is a home for grief —a place where sorrow is acknowledged and transformed. Schubert lays bare his grief — for his impending death, for his sense of isolation as a stranger to the world he loves. Schubert invites us to sit with our pain, and in doing so, shows us that there is light even in the darkest of places.

Rachel Fenlon is a Canadian soprano and pianist who has made a name for herself internationally by performing self-accompanied song recitals. Her debut album, Winterreise, released in October 2024, received critical acclaim, being named Album of the Week by CBC Canada and BBC Radio 3, and Album of the Month by Classic 106 FM. Rachel has performed at prestigious venues including the Martha Argerich Festival, Virtuosi Brazil, Fundación Juan March Madrid, Vancouver Recital Society, Oxford Lieder Festival, and Konzerthaus Berlin, among others.

A Dream of Love Reciprocated: History & the Image by William Kentridge

Written in January, 2014. Printed and redacted with the author’s permission. To read the entire article click here or to watch Mr. Kentridge lecture on his Winterreise at the University of Chicago click here.

Am I too loud?

Johannesburg, Sunday afternoons after lunch. The hiss of the gramophone needle on the record. The indrawn breath before the music. My father lying on the hard sofa, reading the notes on the record sleeve, overstuffed cushion under his head. The yellow and black label of the Deutsche Grammophon Gesselschaft. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau the voice, and the piano of Gerald Moore. An English-German offering, as if to show the war really was over.

This was in the 1960s, where in my family it was still out of the question to buy a German car, or even visit Germany or Austria. Sometimes my mother would be in the room, but more often than not, she would leave. She never liked Lieder, but tolerated it for my father’s sake. She even went to concerts with him. But when she turned 50, she claimed the right never to have to go to another Lieder recital or another Wagner opera.

Checkpoint Charlie

In 1981 I visited Berlin, the first time I had been in Germany. I crossed into East Berlin through Checkpoint Charlie. This was a crossing into a strange world of history and fiction. The crossing itself like walking into a film set from The Spy Who Came In from the Cold. But the city on the other side felt strange, transported through time. The piles of rubble, the empty blocks, and particularly the bullet-riddled surfaces of every building made the fact of the war, the destruction of the city, immediate. But not necessarily real. It was not clear which was the front of the stage, and which was backstage. The modern technology and buildings of West Berlin, being the backstage machinery, there to present the spectacle of ruin and the history in the East; or if East Berlin was the creaking basis and support of the shiny film set of West Berlin, the top floor of the Ka De We being the setting for the last act of the opera.

The city was so overloaded. Between the buildings, the stones, the piles of masonry, the weeds growing in empty lots – between all this and my eyes was such a mass of images, stories, histories. Even looking at the buildings themselves felt like a second-hand looking. It was also the experience of a Johannesburg boy venturing into the forbidden terrain of the other side of the iron curtain (a geography excluded for South Africans because of our apartheid policies; at that time western Europe saw Mandela as a terrorist, and support for Mandela and opposition to the apartheid government came mostly from the USSR and DDR). And let it be said – there was another displacement, even in 1981 that put me on edge: that of being a Jew in German terrain.

This is a biographical start to a talk on image and history – by which I mean, what happens when the world comes into the studio. While thinking where to begin on this topic, I have been working on a project made around a performance of the song cycle Winterreise, by Schubert.

Why Winterreise? It started as a thought of making a cycle of films, like a cycle of songs. I thought of the music of Satie or other early 20th century music. To test ideas I started to look at pieces of film I had already made, whilst listening to different pieces of music. One of the pieces of music I tested was Winterreise, vestigially familiar from childhood.

Drawing in Words

On those Sunday afternoons with my father there was the red and black Penguin book of Lieder, a bilingual edition. I tried to read some of it. It was like reading a prayer book. Each phrase or sentence was comprehensible, but taken together, it became impenetrable. A wall of words that stopped understanding (I would have been between twelve and fifteen at the time). I remember wondering why a song went from such lyricism to shouting and back – feeling that there must be a pattern or logic behind the songs, but not feeling a strong desire to seek out the text. The text was of course important, but the song was much more than the text.

In primary school music lessons, we had learned to sing “Die Forelle” in English. Even then, I felt a gap between the flow and run of the piano, and the awkwardness of the words that we sang. ‘A brooklet clear was running’ (‘In einem Bächlein helle da schoß in froher Eil’). Nobody spoke like that. A brooklet? (There are no brooks near Johannesburg. Ditches. Muddy streams. But no brooks.) There was a gulf between the insistent, contagious, even inevitable nature of the music and the words – the fact of their specificity. The voice must sing the words, but we hear and don’t hear the words. We are caught somewhere in the space between the piano, the words and our imagining.

What to draw?

The first material I started on for the films was stilted, halted by the words of the songs. I needed to draw a gate, I needed to draw snow (and it has only snowed five times in the 58 years of my life in Johannesburg; who was I to draw snow?), I needed to draw a weather vane.

I stopped pushing in this way and looked at what I had drawn without thinking about Winterreise. A series of revolving transforming sculptures already there, turning into a weather vane. The black paper confetti I had used in several earlier films was already snow falling. I had not drawn a Leiermann or a pianola, but I had some years ago used the punched holes of a pianola roll in a film. These now became (they were already were) either a different snow slowly descending or the ice of “Gefror’ne Tränen.”

Music as exemplified by the piano has obvious similarities to film. A transformation of time into palpable material, the frames of the film the notes of the piano. In some of the films for Winterreise, a flipbook technique is used. Pages of the book change for each frame of the film. The rapidly turning pages of the flipbook films I had made became the speed of the fingers of the pianist, the abundance of notes coming from the piano.

In each case, the found image was stronger. Images pushed into service for another idea, but hinting at or coming back with some connection. The instability of a sculpture which was either a telephone or a woman, and the instability of emotion in “Die Wetterfahne.” New material has been drawn for many films, some made entirely new, but generally the pieces that feel strongest are where the music and images amplify each other, and are found rather than made.

The Winterreise project is a trio: a pianist, a singer, the projector. But also a trio of music, text and images. The question of what has primacy – prima la musica, dopo le parole – has been at the heart of opera, a question still unresolved and unresolvable. The imposition of images, fundamental in opera, but not the norm in a song recital, complicates but does not change the fundamental question: what is the space the song occupies in us? The uncharted tension between the limited exactness of the words, and the specific but unplottable meaning of the music: an internal space for the construction of sense.

There is both an ignorance (of language and of tradition) and an inward pressure to connect to the musical event using whatever means possible. This is not to celebrate incomprehension, but an argument for the irrational, unstructured way we make meaning.

Who Needs the Words?

Roland Barthes in his essay ‘The Grain of the Voice’, an essay about Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, makes the distinction between the ‘theno-song’ and the ‘geno-song’. He characterizes the theno-song, as exemplified by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, as singing tied to the dictionary, too based on a clarity of diction of the singer, as if the key to the song is to get the listener to hear every word – so clearly that they cannot avoid ‘the brooklet clear’ of the track. The geno-song (which Barthes hears in the voice of Charles Panzera, the Swiss baritone) is characterized by a voluptuousness, clarity of diction being secondary to the embodiment of the music. The voice, rather than just finding meaning, has to give form to the ‘jouissance’ of the music, the ‘unstable landing point of that desire, joy, or individual thrill’ we feel but find difficult to put into words, that music gives us. The erotic, sensuous charge that music evokes on hearing not just in the head. But Barthes’s argument is also against the perfection of high-fidelity long-playing records, as opposed to the crackly instability of pre-World War II 78 rpm recordings of Panzera. He is longing for a familiar sound, for a graininess. The logical argument is always mired in nostalgia, a private memory inseparable from objective pronouncement – in this case the sounds of the record that Barthes had grown up with and was familiar with.

Working on the Winterreise project – making or finding images for the music – the closest I would come to being a musician – is also about reclaiming those Sunday afternoons, the smell of the cherrywood cabinet, with its neatly labeled drawers for records (Drawer 5: Schubert – not Lieder; Drawer 5a: Lieder (including Wolf and Schumann)). But it is also an after the fact justification of defense of the ‘half-understood’.

I have the text of all the Winterreise songs, in German, in English. I do know the meaning of each of them. The poetry is not dense, the sense not complex. But still while working on each song, I find myself back in the old way of listening to Lieder – a title, a direction, and then the specifics of each line retreating in a mist of incomprehension. I can and do deliberately lift this mist; but always, as I let it drop, I feel closer to the music, closer to each song. I am aware this is precarious terrain: a celebration of incomprehension. I cannot disguise ignorance, in my case ignorance of the German language, which is a lack. But I want to redeem that with the imaginative gain this lack produces.

I am aware this is a Johannesburg perspective. A projection onto the given of the work. The record is like a letter from another world. But there is always distancing. Caspar David Friedrich’s landscapes are both depictions of what he saw, but also constructions made from notes made in his notebooks – ‘ice on a leaf’, the particular form of the angle of separation of branches.

Even in the Vienna of Schubert there is a distancing. Müller, the poet, was very affected by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and his ongoing theme of the traveler walking to his death in the frozen landscape owes much to the image of Frankenstein’s monster on the ice floes at the end of the novel.

This is obvious with painting or writing. What is less obvious is the way this artifice is the model of how we all go through and apprehend the world.

There is the domestic comfort of the Schubertiade, a place of sanctuary in Metternich’s Vienna, a safe space out of the censorship that controlled and confined public space. The rural life in the songs was even then a view of a life idealized and abandoned.

And then there is the gap between the music and the words – the specific words being necessary but inessential. The precise, inarticulateness of the music, the instability being its truth. This is not to claim that music is the unconscious of the song, the truth behind the ostensible meaning of the words; but to make a space for other words and thoughts that the music invokes. To listen to the songs is not to invent lyrics for them, but to enter into a space of specific openness – a precision of meaning one knows is there – the singer had to know the words (as the Rabbi had to know the words of the Hebrew prayers in schul, but we did not).

As a listener one floats between the precision of the piano and words into an area of openness. Not having to visualize a trout in a river, but rather to sense in the music the ripples up and down our own thorax. (If I have to pull a visual image from listening to the trout now, it would be not of a river, but of Mr Reyneke, our music teacher, in his grey three-piece suit, sitting at the piano on stage, and 46 boys in shorts sitting on the floor below him, in the school hall.)

In the films I have made over the years, there has always been a movement between drawing and listening. Showing early stages of the film to the composer (for most films, the composer Philip Miller), and then both of us adjusting our work successively, as the music is written and new image emerge. With Winterreise the process was one not so much of making new drawings, though there are those too, but finding connections: rhythmic, textual, iconic, that felt a good meeting between the songs, written in Vienna in the 1820s and images made in South Africa 180 years later. Not finding (nor looking for) illustrations of the songs – drawing a gate when the word ‘gate’ is heard, or a mountain, or a river – or even directly translating them – a mine dump for a mountain, a storm water drain for a river. Then what? Finding broader corollaries. Films of walking. The bleached Highveld landscape for the snow filled white landscape of the songs.

The shock has been to find a Winterreise that was sitting somewhere in me all these years – as if I had been drawing the project for twenty years. Discovering in working on the songs part of what the films had been all along. This has been the case with other projects too. While working on a production of Gogol’s short story as Shostakovich’s opera The Nose, I found the same thing – I had been had been drawing the opera for years before I came to it. One could do a tracking back of the history of The Nose in the same way as I have done for Winterreise. There is both an image of history, but also a history of the image, which cannot be separated from it.

William Kentridge (born Johannesburg, South Africa, 1955) is one of the world’s leading contemporary artists. His work has been seen in museums and galleries around the world including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Albertina Museum in Vienna, Musée du Louvre in Paris, and countless others. His opera productions including Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Shostakovich’s The Nose, and Alban Berg’s operas Lulu and Wozzeck have been seen at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, La Scala in Milan, and the Salzburg Festival.

This season, his production of Wozzeck can be seen at the Canadian Opera Company from April 25th-May 16th. Learn more at www.kentridge.studio/ and head to Medici.tv to watch Kentridge’s entire Winterreise with Matthias Goerne and Markus Hinterhäuser from Aix-en-Provence.

Daniel Black’s Six Love Songs of Pablo Neruda (2020, orchestrated 2024) by Daniel Black, composer & conductor

Those looking to add Spanish-language art songs to your repertoire might consider my Six Love Songs of Pablo Neruda. The original version is for soprano and piano, although a transposition for low voice is also available. With a total duration of around 23 minutes, each song sets a different poem from Chilean poet Pablo Neruda’s 100 Love Sonnets. I composed this cycle in the summer of 2020 after a chance encounter with the Neruda collection at a used bookstore in Kitchener, Ontario. Neruda’s poems immediately struck me with their depth, beauty, variety, and universal humanity. My song cycle places particular emphasis on clarity and expressiveness of the vocal line with simple harmonic accompaniment. I endeavoured to express the emotions of Neruda’s beautiful words exploring love from a different angles; from the dreamy nostalgia of the first song (« Amor, cuantos caminos hasta llegar a un beso »), to the sense of shared humanity in the second (« Radiantes días »), the naturalism of the third (« Pero, olvidé que tus manos »), the fierce empathy of the fourth (« Espinas, vidrios rotos »), the wistful sadness of the fifth, to the cosmic optimism of the sixth (Y esta palabra, este papel escrito »). Piano-vocal scores are available at www.jwpepper.com.

Daniel Black is a Montreal-based conductor and composer whose works have been performed on three continents. A three-time recipient of the Solti Foundation’s U.S. Career Assistance Award, Daniel has held conducting positions with The Florida Orchestra and the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra and has guest-conducted across the United States, Canada, the Ukraine, and Russia. His composition mentors have included Richard Danielpour, François-Hugues Leclair, and Ana Sokolovic.

Editor’s note: Readers, do you have a little known song cycle you’d like to share with the Art Song Canada community? Write to us at [email protected] to be featured!